W

WAncient South Arabian art was the art of the Pre-Islamic cultures of South Arabia, which was produced from the 3rd millennium BC until the 7th century AD.

W

WThe arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foliate ornament, used in the Islamic world, typically using leaves, derived from stylised half-palmettes, which were combined with spiralling stems". It usually consists of a single design which can be 'tiled' or seamlessly repeated as many times as desired. Within the very wide range of Eurasian decorative art that includes motifs matching this basic definition, the term "arabesque" is used consistently as a technical term by art historians to describe only elements of the decoration found in two phases: Islamic art from about the 9th century onwards, and European decorative art from the Renaissance onwards. Interlace and scroll decoration are terms used for most other types of similar patterns.

W

WAn Arabian carpet is an oriental carpet made in the Arab world using traditional Arab carpet-making techniques. Arabian rugs achieved worldwide fame with the frequent use of the Spice Road.

W

WArabic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy based on the Arabic alphabet. It is known in Arabic as khatt, derived from the word 'line', 'design', or 'construction'. Kufic is the oldest form of the Arabic script.

W

WArabic miniatures are small paintings on paper, usually book or manuscript illustrations but also sometimes separate artworks. The earliest date from around 1000 AD, with a flourishing of the artform from around 1200 AD.

W

WThe Baghdad School, also known as the Arab school, was a relatively short-lived yet influential school of Islamic art developed during the late 12th century in the capital Baghdad of the ruling Abbasid Caliphate. The movement had largely died out by the early 14th century, five decades following the invasion of the Mongols in 1258 and the downfall of the Abbasids' rule, and would eventually be replaced by stylistic movements from the Mongol tradition. The Baghdad School is particularly noted for its distinctive approach to manuscript illustration. The faces depicted in illustrations were individualized and expressive, with the scenes often highlighting realistic features of everyday life from the period. This stylistic movement used strong, bright colors, and employed a balanced sense of design and a decorative quality, with illustrations often lacking traditional frames and appearing between lines of text on manuscript pages.

W

WDamask is a reversible figured fabric of silk, wool, linen, cotton, or synthetic fibers, with a pattern formed by weaving. Damasks are woven with one warp yarn and one weft yarn, usually with the pattern in warp-faced satin weave and the ground in weft-faced or sateen weave. Twill damasks include a twill-woven ground or pattern.

W

WBaron Leo Frédéric Alfred d'Erlanger, also Leo Friedrich Alfred Baron von Erlanger was an English merchant banker and air transport promoter, Chairman of the Erlanger Bank and of the Channel Tunnel Company.

W

WFatimid art refers to [ artifacts and architecture from the Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171), was in Arab empire principally in Egypt and North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate was initially established in the Maghreb, with its roots in a ninth-century Shia Ismailist Many monuments survive in the Fatimid cities founded in North Africa, starting with Mahdia, on the Tunisian coast, the principal city prior to the conquest of Egypt in 969 and the building of al-Qahira, the "City Victorious", now part of modern-day Cairo. The period was marked by a prosperity amongst the upper echelons, manifested in the creation of opulent and finely wrought objects in the decorative arts, including carved rock crystal, lustreware and other ceramics, wood and ivory carving, gold jewelry and other metalware, textiles, books and coinage. These items not only reflected personal wealth, but were used as gifts to curry favour abroad. The most precious and valuable objects were amassed in the caliphal palaces in al-Qahira. In the 1060s, following several years of drought during which the armies received no payment, the palaces were systematically looted, the libraries largely destroyed, precious gold objects melted down, with a few of the treasures dispersed across the medieval Christian world. Afterwards Fatimid artifacts continued to be made in the same style, but were adapted to a larger populace using less precious materials.In 1067-68 the great treasury of the Fatimids was ransacked when the troops rebelled and demanded to be paid. The stories of this plundering mention not only great quantities of pearls and jewels, crowns, swords, and other imperial accoutrements but also many objects in rare materials and of enormous size. Eighteen thousand pieces of carved rock crystal and cut glass were swiftly looted from the palace, and twice as many jewelled objects; also large numbers of gold and silver knives all richly set with jewels; valuable chess and backgammon pieces; various types of hand mirrors, skilfully decorated; six thousand perfume bottles in gilded silver; and so on. More specifically, we learn of enormous pieces of rock crystal inscribed with caliphal names; of gold animals encrusted with jewels and enamels; of a large golden palm tree; and even of a whole garden partially gilded and decorated with niello. There was also an immensely rich treasury of furniture, carpets, curtains, and wall coverings, many embroidered in gold, often with designs incorporating birds and quadrupeds, kings and their notables, and even a whole range of geographical vistas.Relatively few of these objects have survived, most of them very small; but the finest are impressive enough to lend substance to the vivid picture painted in the historical accounts of this vanished world of luxury.

W

WGirih are decorative Islamic geometric patterns used in architecture and handicraft objects, consisting of angled lines that form an interlaced strapwork pattern.

W

WKufic script is a style of Arabic script that gained prominence early on as a preferred script for Quran transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a reference and an archetype for a number of other Arabic scripts. It developed from the Nabataeans of Iraq alphabet in the city of Kufa, from which its name is derived. Kufic script is characterized by angular, rectilinear letterforms and its horizontal orientation. There are many different versions of Kufic script, such as square Kufic, floriated Kufic, knotted Kufic, and others.

W

WThe "Luck of Edenhall" is an enamelled glass beaker that was made in Syria or Egypt in the middle of the 14th century, elegantly decorated with arabesques in blue, green, red and white enamel with gilding. It is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and is 15.8 cm high and 11.1 cm wide at the brim. It had reached Europe by the 15th century, when it was provided with a decorated stiff case in boiled leather with a lid, which includes the Christian IHS; this no doubt helped it to survive over the centuries.

W

WThe Mshatta Facade is the decorated part of the facade of the 8th-century Umayyad residential palace of Qasr Mshatta, one of the Desert Castles of Jordan, which is now installed in the south wing of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany. It is part of the permanent exhibition of the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art dedicated to Islamic art from the 8th to the 19th centuries. This was only a relatively small section of the full length of the facade, surrounding the main entrance; most of the wall was undecorated and remains in situ.

W

WNabataean art is the art of the Nabataeans of North Arabia. They are known for finely-potted painted ceramics, which became dispersed among Greco-Roman world, as well as contributions to sculpture and Nabataean architecture. Nabataean art is most well known for the archaeological sites in Petra, specifically monuments such as Al Khazneh and Ad Deir.

W

WThe term Norman–Arab–Byzantine culture, Norman-Sicilian culture or, less inclusively, Norman–Arab culture, refers to the interaction of the Norman, Latin, Arab and Byzantine Greek cultures following the Norman conquest of Sicily and of Norman Africa from 1061 to around 1250. The civilization resulted from numerous exchanges in the cultural and scientific fields, based on the tolerance showed by the Normans towards the Greek-speaking populations and the Muslim settlers. As a result, Sicily under the Normans became a crossroad for the interaction between the Norman and Latin Catholic, Byzantine–Orthodox and Arab–Islamic cultures.

W

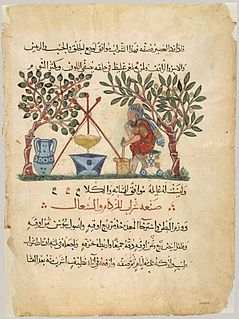

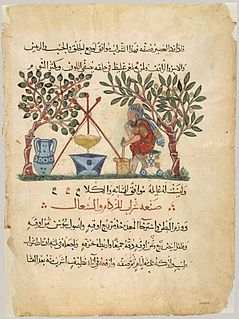

WThe Physician Preparing an Elixir is a miniature on a folio from an illustrated manuscript copy, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York of De Materia Medica, a large herbal or work on the (mostly) medical uses of plants originally written by the ancient Greco-Roman physician, Pedanius Dioscorides, in the first century AD. This page of the manuscript, dated 1224 AD, is made from paper, sized 24.8 cm wide and 33.2 cm long, and is decorated by opaque watercolor, ink, and gold detailing. It is visually split into three horizontal portions from the top of the page to the bottom; the top of the page is dominated by two lines of Arabic script, followed by the image and then five more lines of text in Arabic. The writing below the image is predominantly black with the exception of one line, which is written in red ink and is therefore highlighted to the viewer. The page is usually not on display.

W

WThe Pisa Griffin is a large bronze sculpture of a griffin, a mythical beast, that has remained in Pisa, Italy since the Middle Ages despite its Islamic origin, specifically 11th century Al-Andalus. The Pisa Griffin is the largest medieval Islamic metal sculpture known, standing over three feet tall. It has been described as the "most famous as well as the most beautiful and monumental example" of a tradition of zoomorphic bronzes in Islamic art. The griffin is now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Pisa. The griffin seems at first a historical anomaly given its elusive origin and multiplicity of possible uses, including a fountainhead or musical instrument. However, its possible origin can be approximated by comparing it to similar sculptures of its time, namely the animalistic sculptures and fountains of Al-Andalusian palatial settlements. Furthermore, the griffin may share a similar method of construction, and therefore origin, as the Al-Andalusian fountainheads based on the metallic contents of its bronze alloy.

W

WPseudo-Kufic, or Kufesque, also sometimes Pseudo-Arabic, is a style of decoration used during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, consisting of imitations of the Arabic Kufic script, or sometimes Arabic cursive script, made in a non-Arabic context: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration". Pseudo-Kufic appears especially often in Renaissance art in depictions of people from the Holy Land, particularly the Virgin Mary. It is an example of Islamic influences on Western art.

W

WThe pyxis made in 968 CE/357AH for Prince al-Mughira is a portable ivory carved container that dates from Medieval Islam's Spanish Umayyad period. It is in the collection of the Louvre in Paris. The container was made in one of the Madinat al-Zahra workshops, near modern-day Cordoba, Spain and is thought to have been a coming-of-age present for the son of caliph 'Abd al-Rahman III. Historical sources say that the prince referred to as al-Mughira was Abu al-Mutarrif al-Mughira, the last born son of the caliph ‘Abd al-Rahman III, born to a concubine named Mushtaq. We are certain this pyxis belongs to al-Mughira because of the inscription around the base of the lid which reads: “Blessing from God, goodwill, happiness and prosperity to al-Mughīra, son of the Commander of the Faithful, may God's mercy [be upon him], made in the year 357"

W

WThe Pyxis of Zamora is an carved ivory casket (pyx) that dates from the Caliphate of Córdoba. It is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid, Spain.

W

WTimthal Baghdad is a public monument in Baghdad, created by the sculptor, Mohammed Ghani Hikmat (1929-2011) and inaugurated in 2013. It is a tall column with a woman dressed in Abassid costume sitting on the top. The column is inscribed with Arabic letters, taken from a famous Arabic poem by eminent poet, Mustafa Jamal al-Din. The statue is intended to glorify both the city and its ancient heritage.

W

WZellīj is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces set into a plaster base. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form elaborate geometric motifs, such as radiating star patterns. This form of Islamic art is one of the main characteristics of Moroccan architecture and medieval Moorish architecture. Zellij became a standard decorative element along lower walls, in fountains and pools, and for the paving of floors. It is found commonly in historic buildings throughout the region, as well as in modern buildings making use of traditional designs such as the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca which adds a new color palette with traditional designs.