W

WThe United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

W

WAboriginal title in California refers to the aboriginal title land rights of the indigenous peoples of California. The state is unique in that no Native American tribe in California is the counterparty to a ratified federal treaty. Therefore, all the Indian reservations in the state were created by federal statute or executive order.

W

WAboriginal title statutes in the Thirteen Colonies were one of the principal subjects of legislation by the colonial assemblies in the Thirteen Colonies. With the exception of Delaware, every colony codified a general prohibition on private purchases of Native American lands without the consent of the government. Disputes were generally resolved by special interest legislation or war. Mohegan Indians v. Connecticut (1705–73), a lawsuit that proceeded for 70 years under special royal enabling acts only to be dismissed on non-substantive grounds, was the first and only judicial test of indigenous tenure.

W

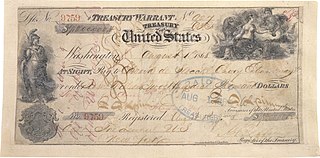

WThe Alaska Purchase was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a treaty ratified by the United States Senate.

W

WThe Black Hawk Purchase, which can sometimes be called the Forty-Mile Strip or Scott's Purchase, extended along the West side of the Mississippi River from the north boundary of Missouri North to the Upper Iowa River in the northeast corner of Iowa. It was fifty miles wide at the ends, and forty in the middle, and is sometimes called the "Forty-Mile Strip". The land, originally owned by the Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Native American people, was acquired by treaty following their defeat by the United States in the Black Hawk War. After being defeated the Sauk and Mesquakie were forced to relinquish another 2.5 million hectares or and give up their rights to plant, hunt, or fish on the land. The purchase was made for $640,000 on September 21, 1832 and was named for the chief Black Hawk, who was held prisoner at the time the purchase was completed. The Black Hawk Purchase contained an area of 6 million acres (24,000 km²), and the price was equivalent to 11 cents/acre. The region is bounded on the East by the Mississippi River and includes Dubuque, Fort Madison, and present-day Davenport.

W

WThe Black Hills land claim is an ongoing land dispute between Native Americans from the Sioux Nation and the United States government. The land in question was pledged to the Sioux Nation in the Fort Laramie Treaty of April 29, 1868, but effectively nullified without the Nation's consent in the Indian Appropriations Bill of 1876. That bill “denied the Sioux all further appropriation and treaty-guaranteed annuities” until they gave up the Black Hills. A Supreme Court case was ruled in favor of the Sioux in 1980. The Sioux have outstanding issues with the ruling and have not collected the funds. As of 2011, the award was worth over $1 billion. It was eventually acknowledged that Sioux tribes did manage to purchase over 1,900 acres of the Black Hills in November 2012 which included the sacred Pe' Sla site. The Pe Sla' site's federal Indian trust status, which was granted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2016, was acknowledged by Pennington County in 2017.

W

WChanges in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England is a 1983 nonfiction book by historian William Cronon.

W

WThe Connecticut Indian Land Claims Settlement was an Indian Land Claims Settlement passed by the United States Congress in 1983. The settlement act ended a lawsuit by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe to recover 800 acres of their 1666 reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. The state sold this property in 1855 without gaining ratification by the Senate. In a federal land claims suit, the Mashantucket Pequot charged that the sale was in violation of the Nonintercourse Act that regulates commerce between Native Americans and non-Indians.

W

WThe Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act; it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, and Seminole. These tribes had been previously exempt from the 1887 General Allotment Act because of the terms of their treaties. In total, the tribes immediately lost control of about 90 million acres of their communal lands; they lost more in subsequent years.

W

WThe Dawes Act of 1887 regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. It authorized the President of the United States to subdivide Native American tribal communal landholdings into allotments for Native American heads of families and individuals. This would convert traditional systems of land tenure into a government-imposed system of private property by forcing Native Americans to "assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property" that did not previously exist in their cultures. The act would declare remaining lands after allotment as "surplus" and available for sale, including to non-Natives. Before private property could be dispensed, the government had to determine "which Indians were eligible" for allotments, which propelled an "official search for a federal definition of Indian-ness."

W

WThe Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, sometimes known as the Donation Land Act, was a statute enacted in late 1850 by the United States Congress. It was intended to promote homestead settlements in the Oregon Territory. The law, a forerunner of the later Homestead Act, brought thousands of white settlers into the new territory, swelling the ranks of settlers traveling along the Oregon Trail. 7,437 land patents were issued under the law, which expired in late 1855.

W

WMinnie Evans was a tribal chair of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation who successfully defeated termination of her tribe and filed for reparations with the Indian Claims Commission during the Indian termination policy period from the 1940s to the 1960s.

W

WThe Georgia land lotteries were an early nineteenth century system of land redistribution in Georgia. Under this system, white male citizens could register for a chance to win lots of land that had been stolen from the Creek Indians and the Cherokee Nation. The lottery system was utilized by the State of Georgia between the years 1805 and 1833 “to strengthen the state and increase the population in order to increase Georgia's power in the House of Representatives.” Although some other states used land lotteries, none were implemented at the scale of the Georgia contests.

W

WThe Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, officially titled the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic, is the peace treaty that was signed on February 2, 1848, in the Villa de Guadalupe Hidalgo between the United States and Mexico that ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The treaty was ratified by the United States on March 10 and by Mexico on May 19. The ratifications were exchanged on May 30, and the treaty was proclaimed on July 4, 1848.

W

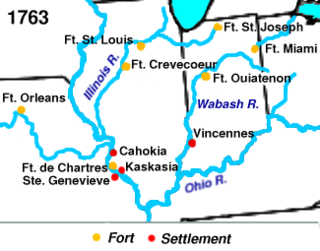

WThe Illinois-Wabash Company, formally known as the United Illinois and Wabash Land Company, was a company formed in 1779 from the merger of the Illinois Company and the Wabash Company. The two companies had been established in order to purchase land from Native Americans in the Illinois Country, a region of North America acquired by Great Britain in 1763. The Illinois Company purchased two large tracts of land in 1773; the Wabash Company purchased two additional tracts in 1775.

W

WIndian country jurisdiction, or the extent which tribal powers apply to legal situations in the United States, has undergone many drastic shifts since the beginning of European settlement in America. Over time, federal statutes and Supreme Court rulings have designated more or less power to tribal governments, depending on federal policy toward Indians. Numerous Supreme Court decisions have created important precedents in Indian country jurisdiction, such as Worcester v. Georgia, Oliphant v. Suquamish Tribe, and Montana v. United States.

W

WIndian Land Claims Settlements are settlements of Native American land claims by the United States Congress, codified in 25 U.S.C. ch. 19.

W

WIndian removal was a forced migration in the 19th century whereby Native Americans were forced by the United States government to leave their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River, specifically to a designated Indian Territory. The Indian Removal Act, the key law that forced the removal of the Indians, was signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, but the law was put into effect primarily under the Martin van Buren administration.

W

WThe Native American Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law authorized the president to negotiate with southern Native American tribes for their removal to federal territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for white settlement of their ancestral lands. The act has been referred to as a unitary act of systematic genocide, because it discriminated against an ethnic group in so far as to make certain the death of vast numbers of its population. The Act was signed by Andrew Jackson and it was strongly enforced under his administration and that of Martin Van Buren, which extended until 1841.

W

WIndian removals in Indiana followed a series of the land cession treaties made between 1795 and 1846 that led to the removal of most of the native tribes from Indiana. Some of the removals occurred prior to 1830, but most took place between 1830 and 1846. The Lenape (Delaware), Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee were removed in the 1820s and 1830s, but the Potawatomi and Miami removals in the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and incomplete, and not all of Indiana's Native Americans voluntarily left the state. The most well-known resistance effort in Indiana was the forced removal of Chief Menominee and his Yellow River band of Potawatomi in what became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838, in which 859 Potawatomi were removed to Kansas and at least forty died on the journey west. The Miami were the last to be removed from Indiana, but tribal leaders delayed the process until 1846. Many of the Miami were permitted to remain on land allotments guaranteed to them under the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818) and subsequent treaties.

W

WThe Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian New Deal". The major goal was to reverse the traditional goal of cultural assimilation of Native Americans into American society and to strengthen, encourage and perpetuate the tribes and their historic Native American cultures in the United States.

W

WAn Indian reservation is a legal designation for an area of land managed by a federally recognized Native American tribe under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs rather than the state governments of the United States in which they are physically located. Each of the 326 Indian reservations in the United States is associated with a particular Native American nation. Not all of the country's 574 federally recognized tribes have a reservation—some tribes have more than one reservation, while some share reservations, and others have no reservations at all. In addition, because of past land allotments, leading to some sales to non–Native Americans, some reservations are severely fragmented, with each piece of tribal, individual, and privately held land being a separate enclave. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.

W

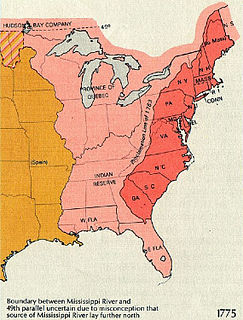

W"Indian Reserve" is a historical term for the largely uncolonized land in North America that was claimed by France, ceded to Great Britain through the Treaty of Paris (1763) at the end of the Seven Years' War—also known as the French and Indian War—and set aside for the First Nations in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The British government had contemplated establishing an Indian barrier state in the portion of the reserve west of the Appalachian Mountains, and bounded by the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and the Great Lakes. British officials aspired to establish such a state even after the region was assigned to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1783) ending the American Revolutionary War, but abandoned their efforts in 1814 after losing military control of the region during the War of 1812.

W

WKeokuk's Reserve was a parcel of land in the present-day U.S. state of Iowa that was retained by the Sauk and Fox tribes in 1832 in the aftermath of the Black Hawk War. The tribes stayed on the reservation only until 1836 when the land was ceded to the United States, and the Native Americans were moved to a new reservation.

W

WThe Narragansett land claim was one of the first litigations of aboriginal title in the United States in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida (1974), or Oneida I, decision. The Narragansett claimed a few thousand acres of land in and around Charlestown, Rhode Island, challenging a variety of early 19th century land transfers as violations of the Nonintercourse Act, suing both the state and private land owners.

W

WThe Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of reservations. The various Acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the Act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

W

WThe Northwest Ordinance enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States. It created the Northwest Territory, the new nation's first organized incorporated territory, from lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains, between British North America and the Great Lakes to the north and the Ohio River to the south. The upper Mississippi River formed the territory's western boundary. Pennsylvania was the eastern boundary.

W

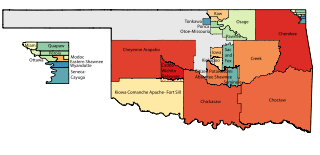

WOklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey. Many of these areas are also designated Tribal Jurisdictional Areas, areas within which tribes will provide government services and assert other forms of government authority. They differ from standard reservations, such as the Osage Nation of Oklahoma, in that allotment was broken up and as a consequence their residents are a mix of native and non-native people, with only tribal members subject to the tribal government. At least five of these areas, those of the so-called five civilized tribes of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole, which cover 43% of the area of the state, are formally recognized as reservations by federal treaty, and thus not subject to state law or jurisdiction for tribal members.

W

WWilliam Lewis Paul was an American attorney, legislator, and political activist from the Tlingit nation of Southeast Alaska. He was known as a leader in the Alaska Native Brotherhood.

W

WThe Platte Purchase was a land acquisition in 1836 by the United States government from American Indian tribes. It comprised lands along the east bank of the Missouri River and added 3,149 square miles (8,156 km2) to the northwest corner of the state of Missouri.

W

WPraying towns were developed by the Puritans of New England from 1646 to 1675 in an effort to convert the local Native American tribes to Christianity. The Natives who moved into these towns were known as Praying Indians. Before 1674 the villages were the most ambitious experiment in converting Native Americans to Christianity in the Thirteen Colonies. John Eliot learned Massachusett and first preached to the Natives in their own language in 1646 at Nonantum, meaning "place of rejoicing." Newton developed here. This sermon led to a friendship with Waban, who became the first Native American in Massachusetts to convert to Christianity.

W

WQuinnatisset was a Nipmuc village in Connecticut which became a praying town through the influence of John Eliot and Daniel Gookin. The town was located near what is now Thompson, Connecticut or Pomfret, Connecticut possibly near Thompson Hill Historic District. The name "Quantisset" means "little long river."

W

WThe Spanish word ranchería, or rancherío, refers to a small, rural settlement. In the Americas the term was applied to native villages or bunkhouses. English adopted the term with both these meanings, usually to designate the residential area of a rancho in the American Southwest, housing aboriginal ranch hands and their families. The term is still used in other parts of Spanish America; for example, the Wayuu tribes in northern Colombia call their villages rancherías.

W

WThe Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on October 7, 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclamation forbade all settlement west of a line drawn along the Appalachian Mountains, which was delineated as an Indian Reserve. Exclusion from the vast region of Trans-Appalachia created discontent between Britain and colonial land speculators and potential settlers. The proclamation and access to western lands was one of the first significant areas of dispute between Britain and the colonies and would become a contributing factor leading to the American Revolution. The 1763 proclamation line is similar to the Eastern Continental Divide's path running northwards from Georgia to the Pennsylvania–New York border and north-eastwards past the drainage divide on the St. Lawrence Divide from there northwards through New England.

W

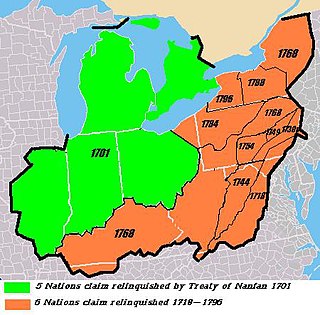

WThe Six Nations land cessions were a series of land cessions by the Iroquois "Six Nations" and Delaware Indians in the late 17th and 18th centuries in which the natives ceded nearly all of their vast conquered lands as well as ancestral land within and adjacent to the northern British colonies of North America. The land cessions covered most or all of the modern states of New York, Pennsylvania, western Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia, Kentucky, northeastern Ohio and extended marginally into northern Tennessee and North Carolina. The lands were bordered to the west by the Algonquin tribal lands of Ohio Country, Cherokee lands to the south, and Creek and other southeastern tribal lands to the southeast.

W

WThe United States Court of Federal Claims is a United States federal court that hears monetary claims against the U.S. government. It is the direct successor to the United States Court of Claims, which was founded in 1855, and is therefore a revised version of one of the oldest federal courts in the country.

W

WThe United States Court of Private Land Claims (1891–1904), was a United States court created to decide land claims guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in the territories of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, and in the states of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming.

W

WThe Walking Purchase was an alleged 1737 agreement between the Penn family, the original proprietors of the Province of Pennsylvania in the colonial era, and the Lenape native Indians. By it the Penn family and proprietors claimed an area of 1,200,000 acres (4,860 km2) along the northern reaches of the Delaware River at the northeastern boundary between the Province of Pennsylvania and the West New Jersey area to the east of the Province of New Jersey and forced the Lenape to vacate it. The Lenape appeal to the Iroquois Indian tribe further north for aid on the issue was refused.

W

WThe Yazoo land scandal, Yazoo fraud, Yazoo land fraud, or Yazoo land controversy was a massive real-estate fraud perpetrated, in the mid-1790s, by Georgia governor George Mathews and the Georgia General Assembly. Georgia politicians sold large tracts of territory in the Yazoo lands, in what are now portions of the present-day states Alabama and Mississippi, to political insiders at very low prices in 1794. Although the law enabling the sales was overturned by reformers the following year, its ability to do so was challenged in the courts, eventually reaching the US Supreme Court. In the landmark decision in Fletcher v. Peck (1810), the Court ruled that the contracts were binding and the state could not retroactively invalidate the earlier land sales. It was one of the first times the Supreme Court had overturned a state law, and it justified many claims for those lands. Some of the land sold by the state in 1794 had been shortly thereafter resold to innocent third parties, greatly complicating the litigation. In 1802, because of the ongoing controversy, Georgia ceded all of its claims to lands west of its modern border to the U.S. government. In exchange the government paid cash and assumed the legal liabilities. Claims involving the land purchases were not fully resolved until legislation was passed in 1814 established a claims-resolution fund.