W

W1q21.1 copy number variations (CNVs) are rare aberrations of human chromosome 1.

W

WApheresis is a medical technology in which the blood of a person is passed through an apparatus that separates out one particular constituent and returns the remainder to the circulation. It is thus an extracorporeal therapy.

W

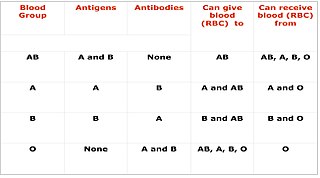

WThe Ashby technique is a method for determining the volume and life span of red blood cells in humans, first published by Dr. Winifred Ashby in 1919. The technique involves injection of compatible donor red blood cells of a different blood group into a recipient, followed by blood testing periodically afterwards. Differential agglutination of the red cells is then used to determine the number of remaining donor cells, allowing the survival rate to be determined. It does not involve radioisotope technology, and was the first technique to successfully establish the correct red blood cell life span. In particular, Type O blood is first transfused into Type A or B subjects. In subsequent blood samples, the patient's own A and B blood cells are removed by agglutination with either anti-A or anti-B serum. The number of remaining nonagglutinated Type O cells as a function of time defines the survival rate of blood cells. This technique was used extensively during World War II and shortly after but has more recently been replaced by techniques that label one's own blood, due of the dangers of using donor blood.

W

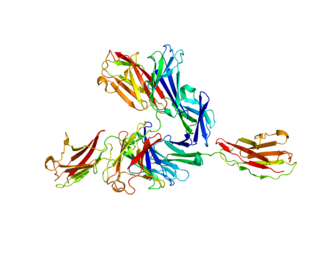

WBasigin (BSG) also known as extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) or cluster of differentiation 147 (CD147) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the BSG gene. This protein is a determinant for the Ok blood group system. There are three known antigens in the Ok system; the most common being Oka, OK2 and OK3. Basigin has been shown to be an essential receptor on red blood cells for the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum.

W

WA Bence Jones protein is a monoclonal globulin protein or immunoglobulin light chain found in the urine, with a molecular weight of 22-24 kDa. Detection of Bence Jones protein may be suggestive of multiple myeloma or Waldenström's macroglobulinemia.

W

WBilirubin glucuronide is a water-soluble reaction intermediate over the process of conjugation of indirect bilirubin. Bilirubin glucuronide itself belongs to the category of conjugated bilirubin along with bilirubin di-glucuronide. However, only the latter one is primarily excreted into the bile in the normal setting.

W

WBlood is a body fluid in humans and other animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

W

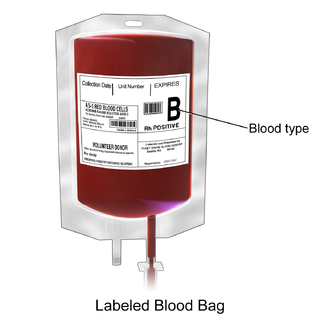

WA blood donation occurs when a person voluntarily has blood drawn and used for transfusions and/or made into biopharmaceutical medications by a process called fractionation. Donation may be of whole blood, or of specific components directly. Blood banks often participate in the collection process as well as the procedures that follow it.

W

WBlood plasma is a yellowish liquid component of blood that holds the blood cells of whole blood in suspension. It is the liquid part of the blood that carries cells and proteins throughout the body. It makes up about 55% of the body's total blood volume. It is the intravascular fluid part of extracellular fluid (all body fluid outside cells). It is mostly water (up to 95% by volume), and contains important dissolved proteins (6–8%) (e.g., serum albumins, globulins, and fibrinogen), glucose, clotting factors, electrolytes (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3−, Cl−, etc.), hormones, carbon dioxide (plasma being the main medium for excretory product transportation), and oxygen. It plays a vital role in an intravascular osmotic effect that keeps electrolyte concentration balanced and protects the body from infection and other blood disorders.

W

WBlood transfusion is the process of transferring blood or blood products into one's circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used whole blood, but modern medical practice commonly uses only components of the blood, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, plasma, clotting factors, and platelets.

W

WA blood type is a classification of blood, based on the presence and absence of antibodies and inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system. Some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of cells of various tissues. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens can stem from one allele and collectively form a blood group system.

W

WBone marrow examination refers to the pathologic analysis of samples of bone marrow obtained by bone marrow biopsy and bone marrow aspiration. Bone marrow examination is used in the diagnosis of a number of conditions, including leukemia, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, anemia, and pancytopenia. The bone marrow produces the cellular elements of the blood, including platelets, red blood cells and white blood cells. While much information can be gleaned by testing the blood itself, it is sometimes necessary to examine the source of the blood cells in the bone marrow to obtain more information on hematopoiesis; this is the role of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

W

WA bruise, also known as a contusion, is a type of hematoma of tissue, the most common cause being capillaries damaged by trauma, causing localized bleeding that extravasates into the surrounding interstitial tissues. Most bruises are not very deep under the skin so that the bleeding causes a visible discoloration. The bruise then remains visible until the blood is either absorbed by tissues or cleared by immune system action. Bruises, which do not blanch under pressure, can involve capillaries at the level of skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or bone. Bruises are not to be confused with other similar-looking lesions. These lesions include petechia, purpura, and ecchymosis.

W

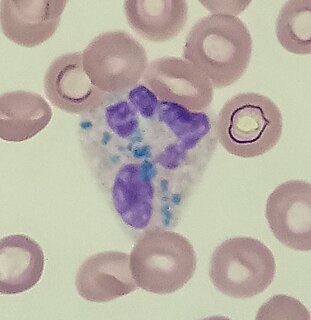

WCigar cells are red blood cells that are cigar- or pencil-shaped on peripheral blood smear. Cigar cells are commonly associated with hereditary elliptocytosis. However, they may also be seen in iron deficiency anemia, sepsis, malaria and other pathological states that decrease red blood cell turnover and or production. In the case of iron deficiency anemia, microcytosis and hypochromia would also be expected.

W

WCritical green inclusions, also known as green neutrophilic inclusions and informally, death crystals or crystals of death, are amorphous blue-green cytoplasmic inclusions found in neutrophils and occasionally in monocytes. They appear brightly coloured and refractile when stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. These inclusions are most commonly found in critically ill patients, particularly those with liver disease, and their presence on the peripheral blood smear is associated with a high short-term mortality rate.

W

WIn transfusion medicine, cross-matching or crossmatching is testing before a blood transfusion to determine if the donor's blood is compatible with the blood of an intended recipient. Cross-matching is also used to determine compatibility between a donor and recipient in organ transplantation. Compatibility is determined through matching of different blood group systems, the most important of which are the ABO and Rh system, and/or by directly testing for the presence of antibodies against the antigens in a sample of donor blood or other tissue.

W

WComplement decay-accelerating factor, also known as CD55 or DAF, is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the CD55 gene.

W

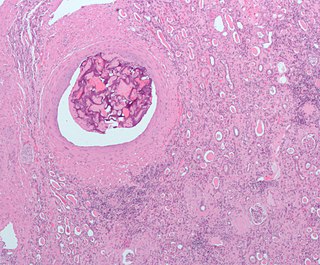

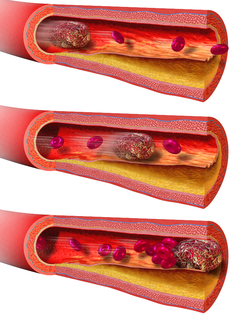

WDeep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs or pelvis. Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and enlarged veins in the affected area, but some DVTs have no symptoms. The most common life-threatening concern with DVT is the potential for a clot to detach from the veins (embolize), travel through the right side of the heart, and become stuck in arteries that supply blood to the lungs. This is called pulmonary embolism (PE). Both DVT and PE are considered as part of the same overall disease process, which is called venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE can occur as DVT only, as PE with DVT, or PE without DVT. The most frequent long-term complication is post-thrombotic syndrome, which can cause pain, swelling, a sensation of heaviness, itching, and in severe cases, ulcers. Also, recurrent VTE occurs in about 30% of those in the ten years following an initial VTE.

W

WAn embolism is the lodging of an embolus, a blockage-causing piece of material, inside a blood vessel. The embolus may be a blood clot (thrombus), a fat globule, a bubble of air or other gas, or foreign material. An embolism can cause partial or total blockage of blood flow in the affected vessel. Such a blockage may affect a part of the body distant from the origin of the embolus. An embolism in which the embolus is a piece of thrombus is called a thromboembolism.

W

WAn embolus is an unattached mass that travels through the bloodstream and is capable of clogging arterial capillary beds at a site distant from its point of origin. There are a number of different types of emboli, including blood clots, cholesterol plaque or crystals, fat globules, gas bubbles, and foreign bodies.

W

WErythroferrone is a protein hormone encoded in humans by the ERFE gene. Erythroferrone is produced by erythroblasts, inhibits the production of hepcidin in the liver, and so increases the amount of iron available for hemoglobin synthesis. Skeletal muscle secreted ERFE has been shown to maintain systemic metabolic homeostasis.

W

WFaggot cells are cells normally found in the hypergranular form of acute promyelocytic leukemia. These promyelocytes have numerous Auer rods in the cytoplasm which gives the appearance of a bundle of sticks, from which the cells are given their name.

W

WIn molecular biology, hemagglutinin or haemagglutinin are glycoproteins which cause red blood cells (RBCs) to agglutinate or clump together. It mostly happens when adding influenza virus to erythrocytes, just as virologist George K. Hirst discovered in 1941, even though it can also occur with measles virus, parainfluenza virus and mumps virus, among others. Time after, more related discoveries were made such as when Alfred Gottschalk proved in 1957 that hemagglutinin links virus in order to host cells by attaching sialic acids on carbohydrate side chains of cell-membrane glycoproteins and glycolipids.

W

WHematidrosis, also called blood sweat, is a very rare condition in which a human sweats blood. The term is from Ancient Greek haîma/haímatos (αἷμα/αἵματος), meaning blood, and hīdrṓs (ἱδρώς), meaning sweat.

W

WHematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) is the transplantation of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells, usually derived from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood. It may be autologous, allogeneic or syngeneic.

W

WPeripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT), also called "Peripheral stem cell support", is a method of replacing blood-forming stem cells destroyed, for example, by cancer treatment. PBSCT is now a much more common procedure than its bone marrow harvest equivalent, this is in-part due to the ease and less invasive nature of the procedure. Studies suggest that PBSCT has a better outcome in terms of the number of hematopoietic stem cell yield.

W

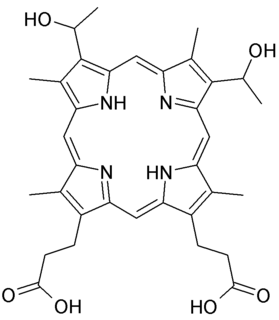

WHematoporphyrin is a porphyrin prepared from hemin. It is a derivative of protoporphyrin IX, where the two vinyl groups have been hydrated. It is a deeply colored solid that is usually encountered as a solution. Its chemical structure was determined in 1900.

W

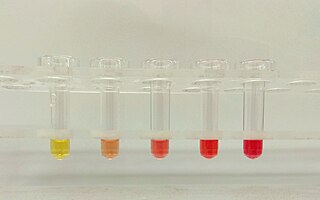

WHemolysis or haemolysis, also known by several other names, is the rupturing (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid. Hemolysis may occur in vivo or in vitro.

W

WHemosiderin or haemosiderin is an iron-storage complex. The breakdown of heme gives rise to biliverdin and iron. The body then traps the released iron and stores it as hemosiderin in tissues. Hemosiderin is also generated from the abnormal metabolic pathway of ferritin.

W

WThomas Hodgkin was a British physician, considered one of the most prominent pathologists of his time and a pioneer in preventive medicine. He is now best known for the first account of Hodgkin's disease, a form of lymphoma and blood disease, in 1832. Hodgkin's work marked the beginning of times when a pathologist was actively involved in the clinical process. He was a contemporary of Thomas Addison and Richard Bright at Guy's Hospital.

W

WThe hook effect or the prozone effect is an immunologic phenomenon whereby the effectiveness of antibodies to form immune complexes is sometimes impaired when concentrations of an antibody or an antigen are very high. The formation of immune complexes stops increasing with greater concentrations and then decreases with extremely high concentrations, producing a hook shape on a graph of measurements. There are versions of the hook effect with excess antibodies and versions with excess antigens. An important practical relevance of the phenomenon is as a type of interference that plagues certain immunoassays and nephelometric assays, resulting in false negatives or inaccurately low results. Other common forms of interference include antibody interference, cross-reactivity and signal interference. The phenomenon is caused by very high concentrations of a particular analyte or antibody and is most prevalent in one-step (sandwich) immunoassays.

W

WHuman iron metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that maintain human homeostasis of iron at the systemic and cellular level. Iron is both necessary to the body and potentially toxic. Controlling iron levels in the body is a critically important part of many aspects of human health and disease. Hematologists have been especially interested in systemic iron metabolism because iron is essential for red blood cells, where most of the human body's iron is contained. Understanding iron metabolism is also important for understanding diseases of iron overload, such as hereditary hemochromatosis, and iron deficiency, such as iron deficiency anemia.

W

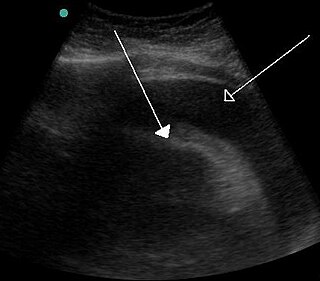

WHypervascularity is an increased number or concentration of blood vessels.

W

WIntrinsic factor (IF), also known as gastric intrinsic factor (GIF), is a glycoprotein produced by the parietal cells of the stomach. It is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 later on in the ileum of the small intestine. In humans, the gastric intrinsic factor protein is encoded by the GIF gene.

W

WJordans' anomaly is a familial abnormality of white blood cell morphology. Individuals with this condition exhibit persistent vacuolation of granulocytes and monocytes in the peripheral blood and bone marrow. Jordans' anomaly is associated with neutral lipid storage diseases.

W

WLeukocyte extravasation is the movement of leukocytes out of the circulatory system and towards the site of tissue damage or infection. This process forms part of the innate immune response, involving the recruitment of non-specific leukocytes. Monocytes also use this process in the absence of infection or tissue damage during their development into macrophages.

W

WLymphoma is a group of blood malignancies that develop from lymphocytes. The name often refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enlarged lymph nodes, fever, drenching sweats, unintended weight loss, itching, and constantly feeling tired. The enlarged lymph nodes are usually painless. The sweats are most common at night.

W

WMusa Mirmammad oglu Abdullayev (27 November 1927, Masallı district, Azerbaijan SSR, USSR — 8 August 1979, Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, USSR) — Prominent hematologist of Azerbaijan, doctor of medicine, professor, philologist-translator. He was one of the eight members of the anti-Soviet nationalist student-youth political organization “Lightning” (İldırım), formed for the independence of Azerbaijan within 1942-1944.

W

WA myeloma protein is an abnormal antibody (immunoglobulin) or a fragment thereof, such as an immunoglobulin light chain, that is produced in excess by an abnormal monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells, typically in multiple myeloma. Other terms for such a protein are M protein, M component, M spike, spike protein, or paraprotein. This proliferation of the myeloma protein has several deleterious effects on the body, including impaired immune function, abnormally high blood viscosity, and kidney damage.

W

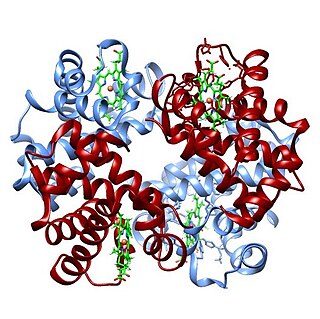

WThe oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve, also called the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve or oxygen dissociation curve (ODC), is a curve that plots the proportion of hemoglobin in its saturated (oxygen-laden) form on the vertical axis against the prevailing oxygen tension on the horizontal axis. This curve is an important tool for understanding how our blood carries and releases oxygen. Specifically, the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve relates oxygen saturation (SO2) and partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PO2), and is determined by what is called "hemoglobin affinity for oxygen"; that is, how readily hemoglobin acquires and releases oxygen molecules into the fluid that surrounds it.

W

WPacked red blood cells, also known as packed cells, are red blood cells that have been separated for blood transfusion. The packed cells are typically used in anemia that is either causing symptoms or when the hemoglobin is less than usually 70–80 g/L. In adults, one unit brings up hemoglobin levels by about 10 g/L. Repeated transfusions may be required in people receiving cancer chemotherapy or who have hemoglobin disorders. Cross matching is typically required before the blood is given. It is given by injection into a vein.

W

WPlasminogen activators are serine proteases that catalyze the activation of plasmin via proteolytic cleavage of its zymogen form plasminogen. Plasmin is an important factor in fibrinolysis, the breakdown of fibrin polymers formed during blood clotting. There are two main plasminogen activators: urokinase (uPA) and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Tissue plasminogen activators are used to treat medical conditions related to blood clotting including embolic or thrombotic stroke, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism.

W

WProtein C, also known as autoprothrombin IIA and blood coagulation factor XIX, is a zymogen, the activated form of which plays an important role in regulating anticoagulation, inflammation, and cell death and maintaining the permeability of blood vessel walls in humans and other animals. Activated protein C (APC) performs these operations primarily by proteolytically inactivating proteins Factor Va and Factor VIIIa. APC is classified as a serine protease since it contains a residue of serine in its active site. In humans, protein C is encoded by the PROC gene, which is found on chromosome 2.

W

WIn hematology, red cell agglutination or autoagglutination is a phenomenon in which red blood cells clump together, forming aggregates. It is caused by the surface of the red cells being coated with antibodies. This often occurs in cold agglutinin disease, a type of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in which people produce antibodies that bind to their red blood cells at cold temperatures and destroy them. People may develop cold agglutinins from lymphoproliferative disorders, from infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Epstein-Barr virus, or idiopathically. Red cell agglutination can also occur in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. In cases of red cell agglutination, the direct antiglobulin test can be used to demonstrate the presence of antibodies bound to the red cells.

W

WRomanowsky staining, also known as Romanowsky–Giemsa staining, is a prototypical staining technique that was the forerunner of several distinct but similar stains widely used in hematology and cytopathology. Romanowsky-type stains are used to differentiate cells for microscopic examination in pathological specimens, especially blood and bone marrow films, and to detect parasites such as malaria within the blood. Stains that are related to or derived from the Romanowsky-type stains include Giemsa, Jenner, Wright, Field, May–Grünwald and Leishman stains. The staining technique is named after the Russian physician Dmitri Leonidovich Romanowsky (1861–1921), who was one of the first to recognize its potential for use as a blood stain.

W

WSuperficial vein thrombosis (SVT) is a type blood clot in a vein, which forms in a superficial vein near the surface of the body. Usually there is thrombophlebitis, which is an inflammatory reaction around a thrombosed vein, presenting as a painful induration with redness. SVT itself has limited significance when compared to a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which occurs deeper in the body at the deep venous system level. However, SVT can lead to serious complications, and is therefore no longer regarded as a benign condition. If the blood clot is too near the saphenofemoral junction there is a higher risk of pulmonary embolism, a potentially life-threatening complication.

W

WTamponade is the closure or blockage by or as if by a tampon, especially to stop bleeding. Tamponade is a useful method of stopping a hemorrhage. This can be achieved by applying an absorbent dressing directly into a wound, thereby absorbing excess blood and creating a blockage, or by applying direct pressure with a hand or a tourniquet.

W

WThrombosis is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel is injured, the body uses platelets (thrombocytes) and fibrin to form a blood clot to prevent blood loss. Even when a blood vessel is not injured, blood clots may form in the body under certain conditions. A clot, or a piece of the clot, that breaks free and begins to travel around the body is known as an embolus.

W

WThrombosis prevention or thromboprophylaxis is medical treatment to prevent the development of thrombosis in those considered at risk for developing thrombosis. Some people are at a higher risk for the formation of blood clots than others. Prevention measures or interventions are usually begun after surgery as people are at higher risk due to immobility.

W

WA thrombus, colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of cross-linked fibrin protein. The substance making up a thrombus is sometimes called cruor. A thrombus is a healthy response to injury intended to prevent bleeding, but can be harmful in thrombosis, when clots obstruct blood flow through healthy blood vessels.

W

WToxic granulation refers to dark coarse granules found in granulocytes, particularly neutrophils, in patients with inflammatory conditions.

W

WToxic vacuolation, also known as toxic vacuolization, is the formation of vacuoles in the cytoplasm of neutrophils in response to severe infections or inflammatory conditions.

W

WIn medicine, venipuncture or venepuncture is the process of obtaining intravenous access for the purpose of venous blood sampling or intravenous therapy. In healthcare, this procedure is performed by medical laboratory scientists, medical practitioners, some EMTs, paramedics, phlebotomists, dialysis technicians, and other nursing staff. In veterinary medicine, the procedure is performed by veterinarians and veterinary technicians.

W

WA venous thrombosis is a thrombosis in a vein, caused by a thrombus. A common type of venous thrombosis is a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which is a blood clot usually found in the deep veins of the leg. It is increasingly found in the deep veins of the arm, accounting for more than 10% of all deep vein thromboses. If the thrombus breaks off (embolizes) and flows towards the lungs, it can become a pulmonary embolism (PE), a blood clot in the lungs. This combination is called venous thromboembolism. Various other forms of venous thrombosis also exist; some of these can also lead to pulmonary embolism.

W

WVirchow's triad or the triad of Virchow describes the three broad categories of factors that are thought to contribute to thrombosis.Hypercoagulability Hemodynamic changes Endothelial injury/dysfunction

W

W