W

WThe French Revolution began in May 1789 when the Ancien Régime was abolished in favour of a constitutional monarchy. Its replacement in September 1792 by the First French Republic led to the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, and an extended period of political turmoil. This culminated in the appointment of Napoleon as First Consul in November 1799, which is generally taken as its end point. Many of its principles are now considered fundamental aspects of modern Liberal democracy.

W

WThe following is a timeline of the French Revolution.

W

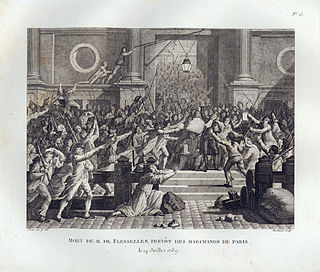

WLanterne is a French word designating a lantern or lamp post. The word, or the slogan "À la lanterne!" gained special meaning and status in Paris and France during the early phase of the French Revolution, from the summer of 1789. Lamp posts served as an instrument to mobs to perform extemporised lynchings and executions in the streets of Paris during the revolution when the people of Paris occasionally hanged officials and aristocrats from the lamp posts. The English equivalent would be "String Them Up!" (British) or "Hang 'Em High!"(American)

W

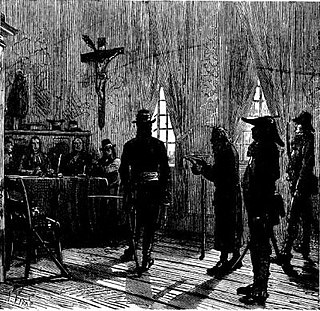

WL'armoire de fer in general refers to an iron chest used to house important papers. A notable and frequent use of the term refers to a hiding place at the apartments of Louis XVI of France at the Tuileries Palace where some secret documents were kept. The existence of this iron cabinet, hidden behind wooden panelling, was publicly revealed in November 1792 to Roland, Girondin Minister of the Interior.

W

WThe Bastille was a fortress in Paris, known formally as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a crowd on 14 July 1789, in the French Revolution, becoming an important symbol for the French Republican movement. It was later demolished and replaced by the Place de la Bastille.

W

WBonnin, Charles-Jean Baptiste Progressive French thinker, theorist, and framer of the modern discipline of Public Administration. From Bonnin's written work a great political and intellectual activity is clear. His academic works credit him as a forerunner of public, constitutional and administrative law. Actually, his 'Social Doctrine' situates him amongst the initiators of the science later known as Sociology. He also practiced parliamentary review and was interested in educational problems. Auguste Comte described Bonnin as a "mature and energetic man, a person with a spontaneous deep kinship for positivism and in whom we can find the true spirit of the Revolution".

W

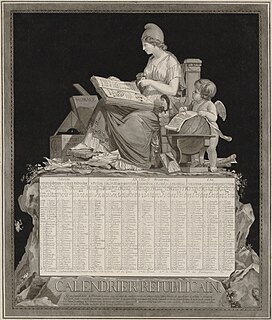

WThe French Republican calendar, also commonly called the French Revolutionary calendar, was a calendar created and implemented during the French Revolution, and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days by the Paris Commune in 1871. The revolutionary system was designed in part to remove all religious and royalist influences from the calendar, and was part of a larger attempt at decimalisation in France. It was used in government records in France and other areas under French rule, including Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Malta, and Italy.

W

WIgnatius Cazeneuve was a constitutional bishop and French politician during the French Revolution. Ignace de Caseneuve of Gap was elected the constitutional bishop of Hautes Alpes on 8 March 1791. He had been a cathedral canon but had gained notoriety as a member of the City Council of Gap in July 1790.

W

WThe Companions of Jehu were formed in the Lyon region of France in April 1795 to hunt down Jacobins implicated in the Reign of Terror. It is possible that they were founded by The Marquis de Besignan, who also founded royalist underground groups in Forez and Dauphiné with the Prince of Condé in 1796. Their victims are believed to have numbered at least in the hundreds. They were made famous by the 1857 novel The Companions of Jehu by Alexandre Dumas which presented a highly romanticised account of them.

W

WThe Conciergerie is a building in Paris, France, located on the west of the Île de la Cité, formerly a prison but presently used mostly for law courts. It was part of the former royal palace, the Palais de la Cité, which consisted of the Conciergerie, Palais de Justice and the Sainte-Chapelle. Hundreds of prisoners during the French Revolution were taken from the Conciergerie to be executed by guillotine at a number of locations around Paris.

W

WThe Demonstration of 20 June 1792 was the last peaceful attempt made by the people of Paris to persuade King Louis XVI of France to abandon his current policy and attempt to follow what they believed to be a more empathetic approach to governing. The demonstration occurred during the French Revolution. Its objectives were to convince the government to enforce the Legislative Assembly's rulings, defend France against foreign invasion, and preserve the spirit of the French Constitution of 1791. The demonstrators hoped that the king would withdraw his veto and recall the Girondin ministers.

W

WPierre Joseph Duhem was a French physician and politician.

W

WHonoré-Nicolas-Marie Duveyrier was an 18th–19th-century French lawyer, politician and playwright.

W

WJean Bertrand Féraud, was a French politician of the French revolutionary era.

W

WThe First French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. Although France had already established a colonial empire overseas since the early 17th century, the French state had remained a kingdom under the Bourbons and a republic after the French Revolution. Historians refer to Napoleon's regime as the First Empire to distinguish it from the restorationist Second Empire (1852–1870) ruled by his nephew Napoleon III.

W

WThe Machecoul massacre is one of the first events of the War in the Vendée, a revolt against mass conscription and the civil constitution of the clergy. The first massacre took place on 11 March 1793, in the provincial city of Machecoul, in the district of the lower Loire. The city was a thriving center of grain trade; most of the victims were administrators, merchants and citizens of the city.

W

WFrench emigration from the years 1789 to 1815 refers to the mass movement of citizens from France to neighboring countries in reaction to the bloodshed and upheaval caused by the French Revolution and Napoleonic rule. Although the Revolution began in 1789 as a peaceful, bourgeois-led effort for increased political equality for the Third Estate, it soon turned into a violent, popular rebellion. To escape political tensions and save their lives, a number of individuals emigrated from France and settled in the neighboring countries, however quite a few also went to the Americas.

W

WIn the history of France, the First Republic, officially the French Republic, was founded on 22 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted until the declaration of the First Empire in 1804 under Napoleon, although the form of the government changed several times. This period was characterized by the fall of the monarchy, the establishment of the National Convention and the Reign of Terror, the Thermidorian Reaction and the founding of the Directory, and, finally, the creation of the Consulate and Napoleon's rise to power.

W

WThe French Revolution is a poem written by William Blake in 1791. It was intended to be seven books in length, but only one book survives. In that book, Blake describes the problems of the French monarchy and seeks the destruction of the Bastille in the name of Freedom.

W

WThe French Revolutionary Army was the French force that fought the French Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1802. These armies were characterised by their revolutionary fervour, their poor equipment and their great numbers. Although they experienced early disastrous defeats, the revolutionary armies successfully expelled foreign forces from French soil and then overran many neighboring countries, establishing client republics. Leading generals included Jourdan, Bonaparte, Masséna and Moreau.

W

WMichael Antoine Garoutte was a member of the first nobility of Provence in the Kingdom of France. He was a Privateer in the early war for American Independence and ascended to the rank of Lieutenant in the first American Continental Navy.

W

WThe Grand Châtelet was a stronghold in Ancien Régime Paris, on the right bank of the Seine, on the site of what is now the Place du Châtelet; it contained a court and police headquarters and a number of prisons.

W

WThe Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on 22 August 1791, and ended in 1804 with the former colony's independence. It involved blacks, mulattoes, French, Spanish, and British participants—with the ex-slave Toussaint Louverture emerging as Haiti's most charismatic hero. The revolution was the only slave uprising that led to the founding of a state which was both free from slavery, and ruled by non-whites and former captives. It is now widely seen as a defining moment in the history of the Atlantic World.

W

WThe Hussards de la Mort or Death Hussars were a French light cavalry company formed during the French Revolution.

W

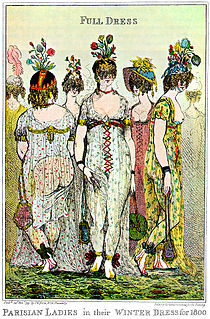

WThe Incroyables and their female counterparts, the Merveilleuses, were members of a fashionable aristocratic subculture in Paris during the French Directory (1795–1799). Whether as catharsis or in a need to reconnect with other survivors of the Reign of Terror, they greeted the new regime with an outbreak of luxury, decadence, and even silliness. They held hundreds of balls and started fashion trends in clothing and mannerisms that today seem exaggerated, affected, or even effete. They were also mockingly called "incoyable" or "meveilleuse", without the letter R, reflecting their posh accent in which that letter was lightly pronounced, almost inaudibly. When this period ended, society took a more sober and modest turn.

W

WThe insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, during the French Revolution, resulted in the fall of the Girondin party under pressure of the Parisian sans-culottes, Jacobins of the clubs, and Montagnards in the National Convention. By its impact and importance, this insurrection stands as one of the three great popular insurrections of the French Revolution, following those of 14 July 1789 and 10 August 1792.

W

WLetters on a Regicide Peace or Letters ... on the Proposals for Peace with the Regicide Directory of France were a series of four letters written by Edmund Burke during the 1790s in opposition to Prime Minister William Pitt's seeking of peace with the revolutionary French Directorate. It was completed and published in 1796.

W

WA liberty pole is a wooden pole, or sometimes spear or lance, surmounted by a "cap of liberty", mostly of the Phrygian cap form outside the Netherlands. The symbol originated in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of the Roman dictator Julius Caesar by a group of Rome's Senators in 44 BC. Immediately after Caesar was killed the assassins, or Liberatores as they called themselves, went through the streets with their bloody weapons held up, one carrying a pileus carried on the tip of a spear. This symbolized that the Roman people had been freed from the rule of Caesar, which the assassins claimed had become a tyranny because it overstepped the authority of the Senate and thus betrayed the Republic.

W

WIn France under the Ancien Régime, the lit de justice was a particular formal session of the Parliament of Paris, under the presidency of the king, for the compulsory registration of the royal edicts. It was named thus because the king would sit on a throne, under a baldachin. In the Middle Ages, not every appearance of the King of France in parlement occasioned a formal lit de justice. It was the custom of Philip IV and his three sons, Charles V, Charles VI, and Louis XII to attend sessions of various parlements regularly.

W

WMarie Lourdais, born in 1761 in Domalain, (Ille-et-Vilaine) was a smuggler, messenger, spy and nurse/medic for the Catholic and Royal armies of the Bas-Poitu, during the French Revolution, namely serving under General François de Charette and General Sapinaud. A grocer in the town of La Gaubretière, she was 30, between 1792–93, when she began aiding the priests in escaping from Nantes; she then joined the Catholic and Royal Army of the Bas-Poitu under Charette in Belleville the same year. She brought news back and forth between the Generals Sapinaud and Charette in the final years of the war. Surviving the War in the Vendée she served Madame de Buor until 1829 and was then taken in by the Mayor of La Gaubretière, M. de Rangot, at whose house she died in 1856 at the age of 95.

W

WThe Lumières was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement of the second half of the 18th century, originating in France and spreading throughout Europe. It included philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza, Denis Diderot, Pierre Bayle and Isaac Newton. Over time it came to mean the Siècle des Lumières, in English the Age of Enlightenment.

W

WThe Musée de la Révolution française is a departmental museum in the French town of Vizille, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south of Grenoble on the Route Napoléon. It is the only museum in the world dedicated to the French Revolution.

W

WThe Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislative Assembly, and the third being the Directory. The Napoleonic era begins roughly with Napoleon Bonaparte's coup d'état, overthrowing the Directory, establishing the French Consulate, and ends during the Hundred Days and his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. The Congress of Vienna soon set out to restore Europe to pre-French Revolution days. Napoleon brought political stability to a land torn by revolution and war. He made peace with the Roman Catholic Church and reversed the most radical religious policies of the Convention. In 1804 Napoleon promulgated the Civil Code, a revised body of civil law, which also helped stabilize French society. The Civil Code affirmed the political and legal equality of all adult men and established a merit-based society in which individuals advanced in education and employment because of talent rather than birth or social standing. The Civil Code confirmed many of the moderate revolutionary policies of the National Assembly but retracted measures passed by the more radical Convention. The code restored patriarchal authority in the family, for example, by making women and children subservient to male heads of households.

W

WThe National Convention was a parliament of the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the one-year Legislative Assembly. Created after the great insurrection of 10 August 1792, it was the first French government organized as a republic, abandoning the monarchy altogether. The Convention sat as a single-chamber assembly from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795.

W

WThe National Guard is a French military, gendarmerie, and police reserve force, active in its current form since 2016 but originally founded in 1789 during the French Revolution.

W

WThe natural borders of France are a political and geographic theory developed in France, notably during the French Revolution. They correspond to the Rhine, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, the Pyrenees and the Alps, according to the revolutionaries.

W

WParis in the 18th century was the second-largest city in Europe, after London, with a population of about 600,000 people. The century saw the construction of Place Vendôme, the Place de la Concorde, the Champs-Élysées, the church of Les Invalides, and the Panthéon, and the founding of the Louvre Museum. Paris witnessed the end of the reign of Louis XIV, was the center stage of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, saw the first manned flight, and was the birthplace of high fashion and the modern restaurant.

W

WA parlement, under the French Ancien Régime, was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 parlements, the oldest and most important of which was the Parlement of Paris. While the English word parliament derives from this French term, parlements were not legislative bodies and the two terms are not interchangeable.

W

WThe Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion between the Tuileries Palace to the north and the Louvre's Grande Galerie to the east. The pavilion was entirely redesigned and rebuilt by Hector Lefuel in 1864–1868 in a highly decorated Napoleon III style. The most famous sculpture on the exterior of the Louvre, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux's The Triumph of Flora, was added below the central pediment of the south facade at this time. The Tuileries Palace was burned by the Paris Commune in 1871, and a north facade, similar to the south facade, was added to the pavilion by Lefuel in 1874–1879. Currently, the Pavillon de Flore is part of the Musée du Louvre.

W

WThe prison de l’Abbaye was a Paris prison in use from 1522 to 1854. The final building was built by Gamard in 1631 and made up of three floors, flanked by two turrets. It was the scene of one of the bloodiest episodes of the French Revolution.

W

WJacques Antoine Rabaut known as Rabaut-Pommier,, was a politician of the French revolutionary era. He was a member of the National Convention (1792–95) and of the Council of Ancients (1795-1801). In 1816 he was exiled for regicide under the Bourbon Restoration, though he later benefited from an amnesty. Deeply committed to medicine, he was an ardent advocate of vaccination.

W

WThe Recollects Convent was built originally in 1684 at the Palace of Versailles, France by order of Louis XIV as a house for the religious order of Recollects - a reform branch of the Franciscans created in 16th century in France, Germany, and Holland. After the order was suppressed during the French Revolution, the building was converted into a prison, and then later in the 19th century was used by the French army.

W

WRevolutionary terror, also referred to as revolutionary terrorism or a reign of terror, refers to the institutionalized application of force to counterrevolutionaries, particularly during the French Revolution from the years 1793 to 1795. The term "Communist terrorism" has also been used to describe the revolutionary terror, from the Red Terror in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) to the reign of the Khmer Rouge and others. In contrast, "reactionary terror", such as White Terror, has been used to subdue revolutions.

W

WAugustin Bon Joseph de Robespierre was the younger brother of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre.

W

WThe indoor riding academy called the Salle du Manège was the seat of deliberations during most of the French Revolution, from 1789 to 1798.

W

WThe sans-culottes were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the Ancien Régime. The word sans-culotte, which is opposed to that of the aristocrat, seems to have been used for the first time on 28 February 1791 by officer Gauthier in a derogatory sense, speaking about a "sans-culottes army". The word came in vogue during the demonstration of 20 June 1792.

W

WThe Society of the Friends of Truth, also known as the Social Club, was a French revolutionary organization founded in 1790. It was "a mixture of revolutionary political club, the Masonic Lodge, and a literary salon". It also published an influential revolutionary newspaper, the Mouth of Iron.

W

WThe Square du Temple is a garden in Paris, France in the 3rd arrondissement, established in 1857. It is one of 24 city squares planned and created by Georges-Eugène Haussmann and Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand. The Square occupies the site of a medieval fortress in Paris, built by the Knights Templar. Parts of the fortress were later used as a prison during the French Revolution, and then demolished by the mid-19th century.

W

WSymbolism in the French Revolution was a device to distinguish and celebrate the main features of the French Revolution and ensure public identification and support. In order to effectively illustrate the differences between the new Republic and the old regime, the leaders needed to implement a new set of symbols to be celebrated instead of the old religious and monarchical symbolism. To this end, symbols were borrowed from historic cultures and redefined, while those of the old regime were either destroyed or reattributed acceptable characteristics. New symbols and styles were put in place to separate the new, Republican country from the monarchy of the past. These new and revised symbols were used to instill in the public a new sense of tradition and reverence for the Enlightenment and the Republic.

W

WA Temple of Reason was, during the French Revolution, a temple for a new belief system created to replace Christianity: the Cult of Reason, which was based on the ideals of reason, virtue, and liberty. This "religion" was supposed to be universal and to spread the ideas of the revolution, summarized in its "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" motto, which was also inscribed on the Temples. According to the conservative critics of the French Revolution, within the Temple of Reason, "atheism was enthroned". English theologian Thomas Hartwell Horne and biblical scholar Samuel Davidson write that "churches were converted into 'temples of reason,' in which atheistical and licentious homilies were substituted for the proscribed service".

W

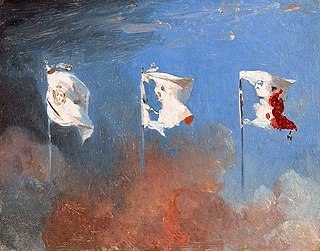

WA tricolour or tricolor is a type of flag or banner design with a triband design which originated in the 16th century as a symbol of republicanism, liberty or indeed revolution. The flags of France, Italy, Romania, Mexico, and Ireland were all first adopted with the formation of an independent republic in the period of the French Revolution to the Revolutions of 1848, with the exception of the Irish tricolour, which dates from 1848 but was not popularised until the Easter Rising in 1916 and adopted in 1919.

W

WThe Tuileries Palace was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from Henry IV to Napoleon III, until it was burned by the Paris Commune in 1871.

W

WHistorians since the late 20th century have debated how women not shared in the French Revolution and what short-term impact it had on French women. Women had no political rights in pre-Revolutionary France; they were considered "passive" citizens, forced to rely on men to determine what was best for them. That changed dramatically in theory as there seemingly were great advances in feminism. Feminism emerged in Paris as part of a broad demand for social and political reform. The women demanded equality to men and then moved on to a demand for the end of male domination. Their chief vehicle for agitation were pamphlets and women's clubs, especially the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women. However, the Jacobin element in power abolished all the women's clubs in October 1793 and arrested their leaders. The movement was crushed. Devance explains the decision in terms of the emphasis on masculinity in wartime, Marie Antoinette's bad reputation for feminine interference in state affairs, and traditional male supremacy. A decade later the Napoleonic Code confirmed and perpetuated women's second-class status.