W

WPre-Columbian Aztec society was a highly complex and stratified society that developed among the Aztecs of central Mexico in the centuries prior to the Spanish conquest of Mexico, and which was built on the cultural foundations of the larger region of Mesoamerica. Politically, the society was organized into independent city-states, called altepetls, composed of smaller divisions (calpulli), which were again usually composed of one or more extended kinship groups. Socially, the society depended on a rather strict division between nobles and free commoners, both of which were themselves divided into elaborate hierarchies of social status, responsibilities, and power. Economically the society was dependent on agriculture, and also to a large extent on warfare. Other economically important factors were commerce, long-distance and local, and a high degree of trade specialization.

W

WThe altepetl was the local, ethnically-based political entity, usually translated into English as "city-state," in pre-Columbian societies. The altepetl was constituted of smaller units known as calpolli and was typically led by a single dynastic ruler known as a tlatoani, although examples of shared rule between up to five rulers are known. Each altepetl had its own jurisdiction, origin story, and served as the center of Indigenous identity. Residents referred to themselves by the name of their altepetl rather than, for instance, as "Aztecs." Altepetl was a polyvalent term rooting the social and political order in the creative powers of a sacred mountain that contained the ancestors, seeds and life-giving forces of the community. The word is a combination of the Nahuatl words ātl and tepētl. A characteristic Nahua mode was to imagine the totality of the people of a region or of the world as a collection of altepetl units and to speak of them on those terms. The concept is comparable to Maya cah and Mixtec ñuu. Altepeme formed a vast complex network which predated and outlasted larger empires, such as the Aztec and Tarascan state.

W

WAmate is a type of bark paper that has been manufactured in Mexico since the precontact times. It was used primarily to create codices.

W

WThe Aztec religion originated from the indigenous Aztecs of central Mexico. Like other Mesoamerican religions, it also has practices such as human sacrifice in connection with many religious festivals which are in the Aztec calendar. This polytheistic religion has many gods and goddesses; the Aztecs would often incorporate deities that were borrowed from other geographic regions and peoples into their own religious practices.

W

WThe Aztec or Mexica calendar is the calendrical system used by the Aztecs as well as other Pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico. It is one of the Mesoamerican calendars, sharing the basic structure of calendars from throughout ancient Mesoamerica.

W

WThe Calmecac was a school for the sons of Aztec nobility in the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, where they would receive rigorous religious and military training. The calmecac tied together the military, political and sacred hierarchies of the community. The two main primary sources for information on the calmecac and telpochcalli are in Bernardino de Sahagún's Florentine Codex of the General History of the Things of New Spain and part 3 of the Codex Mendoza. Although the calmecac has been characterized as for elites only, Sahagun's account says that at times commoners, macehualtin were assigned to the calmecac as well and trained for the priesthood. The Tēlpochcalli was where mostly commoners and some noble youths received military training, but would have been precluded from the higher ranks of power. Codex Mendoza's account of the calmecac emphasizes the possibilities of upward mobility for young commoner men, (macehualtin), educated in the telpochcalli. The placement of noble youth in the telpochcalli might have been by lesser wives' or concubines' sons or younger sons, perhaps of commoner status so that the boys did not have to compete with noble youths in the calmecac. Codex Mendoza's account largely ignores class distinctions between the two institutions.

W

WThe Chimalli was the traditional defensive armament of the indigenous states of Mesoamerica. These shields varied in design and purpose. The Chimali was also used while wearing special headgear.

W

WChinampa is a technique used in Mesoamerican agriculture which relied on small, rectangular areas of fertile arable land to grow crops on the shallow lake beds in the Valley of Mexico. They are built up on wetlands of a lake or freshwater swamp for agricultural purposes, and their proportions ensure optimal moisture retention.

W

WAztec clothing are the fiber of clothing that were worn by the Aztecs peoples during their time that varied based on aspects such as social standing and gender. The garments worn by Aztec peoples were also worn by other pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico who shared similar cultural characteristics. The strict sumptuary laws present in Aztec society had dictated the type of fiber and ornamentation present in clothing, as well as how that clothing was worn based on class. Clothing and cloth were immensely significant in the culture.

W

WThe Codex Mendoza is an Aztec codex, believed to have been created around the year 1541. It contains a history of both the Aztec rulers and their conquests as well as a description of the daily life of pre-conquest Aztec society. The codex is written in the Nahuatl language utilizing traditional Aztec pictograms with a translation and explanation of the text provided in Spanish. It is named after Don Antonio de Mendoza, the viceroy of New Spain, and a leading patron of native artists.

W

WThe Codex Totomixtlahuaca or Codex Condumex is a colonial-era map produced on a large piece of cotton. The map represents Totomixlahuaca, Mexico, and includes a creation date of 1564. It documents a meeting over a land conflict in communities of the current Mexican state of Guerrero.

W

WThe Codex Xolotl is a postconquest cartographic Aztec codex, thought to have originated before 1542. It is annotated in Nahuatl and details the preconquest history of the Valley of Mexico, and Texcoco in particular, from the arrival of the Chichimeca under the king Xolotl in the year 5 Flint (1224) to the Tepanec War in 1427.

W

WAztec cuisine is the cuisine of the former Aztec Empire and the Nahua peoples of the Valley of Mexico prior to European contact in 1519.

W

WThe ancient Aztecs employed a variety of entheogenic plants and animals within their society. The various species have been identified through their depiction on murals, vases, and other objects. The plants used include ololiuqui, teonanácatl, sinicuichi, toloatzin, peyotl and many others.

W

WHuman sacrifice was common in many parts of Mesoamerica, so the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived at the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs, and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations, such as Teotihuacán. What distinguished Maya and Aztec human sacrifice was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life and believed to be a necessity. These cultures also notably sacrificed elements of their own population to the gods.

W

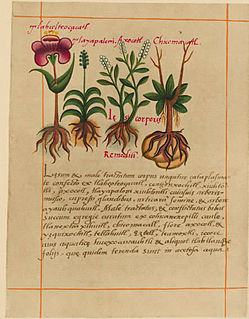

WThe Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis is an Aztec herbal manuscript, describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano, from a Nahuatl original composed in the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1552 by Martín de la Cruz that is no longer extant. The Libellus is also known as the Badianus Manuscript, after the translator; the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, after both the original author and translator; and the Codex Barberini, after Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who had possession of the manuscript in the early 17th century.

W

WAztec medicine concerns the body of knowledge, belief and ritual surrounding human health and sickness, as observed among the Nahuatl-speaking people in the Aztec realm of central Mexico. The Aztecs knew of and used an extensive inventory consisting of hundreds of different medicinal herbs and plants. A variety of indigenous Nahua and Novohispanic written works survived from the conquest and later colonial periods that describe aspects of the Aztec system and practice of medicine and its remedies, incantations, practical administration, and cultural underpinnings. Elements of traditional medicinal practices and beliefs are still found among modern-day Nahua communities, often intermixed with European or other later influences.

W

WThe New Fire Ceremony was an Aztec ceremony performed once every 52 years—a full cycle of the Aztec “calendar round”—in order to stave off the end of the world. The calendar round was the combination of the 260-day ritual calendar and the 365-day annual calendar. This New Fire Ceremony was part of the “Binding of the Years” tradition among the Aztecs.

W

WNopal (from the Nahuatl word nohpalli [noʔˈpalːi] for the pads of the plant) is a common name in Spanish for Opuntia cacti, as well as for its pads.

W

WAztec philosophy was a school of philosophy that developed out of Aztec culture. The Aztecs had a well-developed school of philosophy, perhaps the most developed in the Americas and in many ways comparable to Ancient Greek philosophy, even amassing more texts than the ancient Greeks. Aztec cosmology was in some sense dualistic, but exhibited a less common form of it known as dialectical monism. Aztec philosophy also included ethics and aesthetics. It has been asserted that the central question in Aztec philosophy was how people can find stability and balance in an ephemeral world.

Pochteca were professional, long-distance traveling merchants in the Aztec Empire. The trade or commerce was referred to as pochtecayotl. Within the empire, the pochteca performed three primary duties: market management, international trade, and acting as market intermediaries domestically. They were a small but important class as they not only facilitated commerce, but also communicated vital information across the empire and beyond its borders, and were often employed as spies due to their extensive travel and knowledge of the empire. The pochteca are the subject of Book 9 of the Florentine Codex (1576), compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún.

W

WThe Ramírez Codex is a post-conquest codex from the late 16th century entitled Relación del origen de los indios que hábitan esta Nueva España según sus Historias.

W

WAztec slavery, within the structure of the Mexico society, produced many slaves, known by the Nahuatl word, tlacotin. Within Mexica society, slaves constituted an important class.

W

WIn the Aztec culture, a tecpatl was a flint or obsidian knife with a lanceolate figure and double-edged blade, with elongated ends. Both ends could be rounded or pointed, but other designs were made with a blade attached to a handle. It can be represented with the top half red, reminiscent of the color of blood, in representations of human sacrifice and the rest white, indicating the color of the flint blade.

W

WA temazcal is a type of low heat sweat lodge, which originated with pre-Hispanic Indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica. The term temazcal comes from the Nahuatl word temāzcalli [temaːsˈkalːi], or possibly from the Nahua words teme and calli (house).

W

WA teponaztli [tepoˈnast͡ɬi] is a type of slit drum used in central Mexico by the Aztecs and related cultures.

W

WIn the Aztec military, tlacateccatl was a title roughly equivalent to general. The tlacateccatl was in charge of the tlacatecco, a military quarter in the center of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan. In wartime he was second-in-command to the tlatoani and the tlacochcalcatl. The tlacateccatl was always a member of the military order of the Cuachicqueh, "the shorn ones".

W

WTlacochcalcatl was an Aztec military title or rank; roughly equivalent to the modern title of General. In Aztec warfare the tlacochcalcatl was second in command only to the tlatoani and he usually lead the Aztec army into battle when the ruler was otherwise occupied. Together with the tlacateccatl (general), he was in charge of the Aztec army and undertook all military decisions and planning once the tlatoani had decided to undertake a campaign.

W

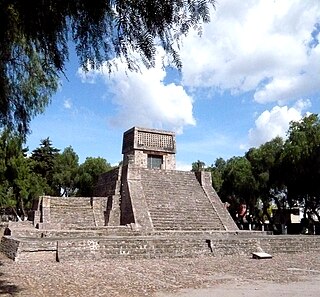

WA tzompantli [t͡somˈpant͡ɬi] or skull rack is a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims. It is a scaffold-like construction of poles on which heads and skulls were placed after holes had been made in them. Many have been documented throughout Mesoamerica, and range from the Epiclassic through early Post-Classic. In 2017 archeologists announced the discovery of the Huey Tzompantli, with more than 650 skulls, in the archeological zone of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

W

WWomen in Aztec civilization shared some equal opportunities. Aztec civilization saw the rise of a military culture that was closed off to women and made their role complementary to men. The status of Aztec women in society was altered in the 15th century, when Spanish conquest forced European norms onto the indigenous culture. However, many pre-Columbian norms survived and their legacy still remains.