W

WAncient Chinese coinage includes some of the earliest known coins. These coins, used as early as the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE), took the form of imitations of the cowrie shells that were used in ceremonial exchanges. The same period also saw the introduction of the first metal coins; however, they were not initially round, instead being either knife shaped or spade shaped. Round metal coins with a round, and then later square hole in the center were first introduced around 350 BCE. The beginning of the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), the first dynasty to unify China, saw the introduction of a standardised coinage for the whole Empire. Subsequent dynasties produced variations on these round coins throughout the imperial period. At first the distribution of the coinage was limited to use around the capital city district, but by the beginning of the Han Dynasty, coins were widely used for such things as paying taxes, salaries and fines.

W

WAnt-nose coin, also called ant nose money, yibi cowry, Yibi coin and so on, was a small bronze coin minted by the state of Chu during the Warring States period. In Chinese, it is also called "鬼脸钱".

W

WBamboo tallies, alternatively known as bamboo tokens or bamboo money, were a type of alternative currency that was produced in Eastern China from the 1870s until the 1940s and were used to supplement Chinese cash coins and other small denomination Chinese currencies in a manner similar to paper money. Some bamboo tallies were issued in denominations of wén (文) or "strings of cash coins" (串), some bamboo tallies were denominated in qián (錢), tóngyuán, jiǎo (角), and yáng, other than in money bamboo tallies could also be dominated in tea bags. During the same time as bamboo tallies were issued other local businesses manufactured paper money denominated in fēn (分) while others used either copper tokens or money made from bones in a similar fashion.

W

WThe Ban Liang was the first unified currency of the Chinese empire, introduced by the first emperor Qin Shi Huang around 210 BC. It was round with a square hole in the middle. Before that date, a variety of coins were used in China, usually in the form of blades or other implements, though round coins with square holes were used by the State of Zhou before it was extinguished by Qin in 249 BCE.

W

WThe banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank, known as the banknotes of the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue from 1905 to 1908, were intended to become the main form of paper money in the Qing currency system. These banknotes were issued by the Ta-Ching Government Bank, a national bank established to serve as the central bank of the Qing dynasty. The Ta-Ching Government Bank had branches throughout China and many of its branches outside of its headquarters in Beijing also issued banknotes.

W

WBingqian, or Bingxingqian, is a term, which translates into English as "biscuit coins", "pie coins", or "cake coins", used by Chinese and Taiwanese coin collectors to refer to cash coins with an extremely broad rim as, these cash coins can also be very thick. While the earliest versions of the Bingqian did not extraordinarily broad rims.

W

WStephen Wootton Bushell CMG MD was an English physician and amateur Orientalist who made important contributions to the study of Chinese ceramics, Chinese coins and the decipherment of the Tangut script.

W

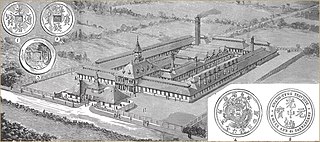

WThe Canton Mint also romanised as Kwangtung Mint was a mint located in Guangdong, China which produced coinage at the discretion of the Canton Provincial government. Opened in 1889 it was the first mint in China that used modern minting techniques and was at the time the largest mint in the world producing 2.7 million coins per day.

W

WCash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD, characterised by their round outer shape and a square center hole. Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast, but during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.

W

WCash coins are a type of historical Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, and Vietnamese coin design that was the main basic design for the Chinese cash, Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn currencies. The cash coin became the main standard currency of China in 221 BC with the Ban Liang (半兩) and would be produced until 1912 AD there with the Minguo Tongbao (民國通寶), the last series of cash coins produced in the world were the French Indochinese Bảo Đại Thông Bảo (保大通寶) during the 1940s. Cash coins are round coins with a square centre hole. It is commonly believed that the early round coins of the Warring States period resembled the ancient jade circles (璧環) which symbolised the supposed round shape of the sky, while the centre hole in this analogy is said to represent the planet earth (天圓地方). The body of these early round coins was called their "flesh" (肉) and the central hole was known as "the good" (好).

W

WThe cash was a currency denomination used in China in imperial times. It was the chief denomination until the introduction of the yuan in the late 19th century.

W

WThe Chinese Gold Panda is a series of gold bullion coins issued by the People's Republic of China. The Official Mint of the People's Republic of China introduced the panda gold bullion coins in 1982. The panda design changes every year and the Gold Panda coins come in different sizes and denominations, ranging from 1⁄20 to 1 troy ounce.

W

WThe Chinese Silver Panda is a series of silver bullion coins issued by the People's Republic of China. The design of the panda is changed every year and minted in different sizes and denominations, ranging from 0.5 troy oz. to 1 kilogram. Starting in 2016, Pandas switched to metric sizes. The 1 troy ounce coin was reduced to 30 grams, while the 5 troy ounce coin was reduced to 150 grams. There is also a Gold Panda series issued featuring the same designs as the Silver Panda coins.

W

WThe list of coin hoards in China lists significant archaeological hoards of coins, other types of coinages or objects related to coins discovered in China. The history of Chinese currency dates back as early as the Spring and Autumn period, and the earliest coinages took the form of imitations of the cowrie shells that were used in ceremonial exchanges. During the Warring States period new forms of currency such as the spade money, knife money, and round copper-alloy coins were introduced. After unification of China under the Qin dynasty in 221 BC the Ban Liang (半兩) cash coin became the standard coinage, under the Han dynasty the Wu Zhu (五銖) cash coins became the main currency of China until they were replaced with the Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) during the Tang dynasty, after which a large number of inscriptions were used on Chinese coinages. During the late nineteenth century China started producing its own machine-struck coinages.

W

WJoe Cribb is a numismatist, specialising in Asian coinages, and in particular on coins of the Kushan Empire. His catalogues of Chinese silver currency ingots, and of ritual coins of Southeast Asia were the first detailed works on these subjects in English. With David Jongeward he published a catalogue of Kushan, Kushano-Sasanian and Kidarite Hun coins in the American Numismatic Society New York in 2015.

W

WThe Da Ming Baochao was a series of banknotes issued during the Ming dynasty in China. They were first issued in 1375 under the Hongwu Emperor. Although initially the Da Ming Baochao paper money was successful, the fact that it was a fiat currency and that the government largely stopped accepting these notes caused the people to lose faith in them as a valid currency causing the price of silver relative to paper money to increase. The negative experiences with inflation that the Ming dynasty had witnessed signaled the Manchus to not repeat this mistake until the first Chinese banknotes after almost 400 years were issued again in response to the Taiping Rebellion under the Qing dynasty's Xianfeng Emperor during the mid-19th century.

W

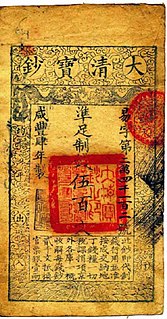

WThe Da-Qing Baochao refers to a series of Qing dynasty banknotes issued under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor issued between the years 1853 and 1859. These banknotes were all denominated in wén and were usually introduced to the general market through the salaries of soldiers and government officials.

W

WThe Da-Qing Jinbi was the name of a unissued series of gold coins produced under the reign of the Guangxu Emperor. These coins were produced in the scenario that the government of the Manchu Qing dynasty would adopt the gold standard, as was common in most of the world at the time.

W

WThe Da-Qing Tongbi, or the Tai-Ching-Ti-Kuo copper coin, refers to a series of copper machine-struck coins from the Qing dynasty produced from 1906 until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911. These coins were intended to replace the earlier cast cash coins and provincial coinages, but were welcomed to mixed receptions.

W

WDaqian are large-denomination cash coins produced in the Qing dynasty starting from 1853 until 1890. Large denomination cash coins were previously used in earlier Chinese dynasties and had faced similar issues as 19th-century Daqian. The term referred to cash coins with a denomination of 4 wén or higher.

W

WThe history of Chinese currency spans more than 3000 years. Currency of some type has been used in China since the Neolithic age which can be traced back to between 3000 and 4500 years ago. Cowry shells are believed to have been the earliest form of currency used in Central China, and were used during the Neolithic period.

W

W"Red cash coins" are the cash coins produced in Xinjiang under Qing rule following the conquest of the Dzungar Khanate by the Qing dynasty in 1757. While in Northern Xinjiang the monetary system of China proper, with standard cash coins, was adopted in Southern Xinjiang where the pūl (ﭘول) coins of Dzungaria circulated earlier the pūl-system was continued but some of the old Dzungar pūl coins were melted down to make Qianlong Tongbao (乾隆通寶) cash coins, as pūl coins were usually around 98% copper they tended to be very red in colour which gave the cash coins based on the pūl coins the nickname "red cash coins".

W

WThe Hongwu Tongbao was the first cash coin to bear the reign name of a reigning Ming dynasty Emperor bearing the reign title of the Hongwu Emperor. Hongwu Tongbao cash coins officially replaced the earlier Dazhong Tongbao coins, however the production of the latter did not cease after the Hongwu Tongbao was introduced. The government of the Ming dynasty placed a greater reliance on copper cash coins than the Yuan dynasty ever did, but despite this reliance a nationwide copper shortage caused the production of Hongwu Tongbao cash coins to cease several times eventually leading to their discontinuation in 1393 when they were completely phased out in favour of paper money. In the year 1393 there were a total of 325 furnaces in operation in all provincial mints of China which had an annual output of 189,000 strings of cash coins which was merely 3% of the average annual production during the Northern Song dynasty.

W

WHorse coins, alternatively dama qian (打馬錢), are a type of Chinese numismatic charm that originated in the Song dynasty and presumed to have been used as gambling tokens. Although many literary figures wrote about these coins their usage has always been failed to be mentioned by them. Most horse coins tend to be round coins, 3 centimeters in diameter with a circular or square hole in the middle of the coin. The horses featured on horse coins are depicted in various positions such as lying asleep on the ground, turning their head while neighing, or galloping forward with their tails rising high. it is currently unknown how horse coins were actually used though it is speculated that Chinese horse coins were actually used as game board pieces or gambling counters. Horse coins are most often manufactured from copper or bronze, but in a few documented cases they may also be made from animal horns or ivory. The horse coins produced during the Song dynasty are considered to be those of the best quality and craftsmanship and tend be made from better metal than the horse coins produced after. Some horse coins would feature the name of the famous horses they depicted. It is estimated that there are over three hundred variants of the horse coin. Some horse coins contained only an image of a horse while others also included an image of the rider and others had inscriptions which identify the horse or rider. During the beginning of the year of the horse in 2002 Chinese researchers Jian Ning and Wang Liyan of the National Museum of Chinese History wrote articles on horse coins in the China Cultural Relics Newspaper, noting that they found it a pity that the holes in the coins covered the saddles of the horses as this could have revealed more about ancient horse culture. Horse coins from the Song dynasty are the horse coins that are produced at the highest quality while horse coins from subsequent dynasties tend to be inferior compared to them.

W

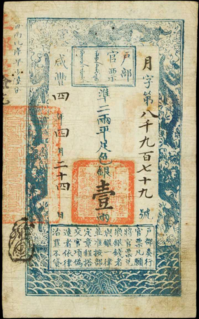

WThe Hubu Guanpiao is the name of two series of banknotes produced by the Qing dynasty, the first series was known as the Chaoguan (鈔官) and was introduced under the Shunzhi Emperor during the Qing conquest of the Ming dynasty but was quickly abandoned after this war ended, it was introduced amid residual ethnic Han resistance to the Manchu invaders. It was produced on a small scale, amounting to 120,000 strings of cash coins annually, and only lasted between 1651 and 1661. After the death of the Shunzhi Emperor in the year 1661, calls for resumption of banknote issuance weakened, although they never completely disappeared.

W

WThe Jin dynasty was a Jurchen-led dynasty of China that ruled over northern China and Manchuria from 1115 until 1234. After the Jurchens defeated the Liao dynasty and the Northern Song dynasty, they would continue to use their coins for day to day usage in the conquered territories. In 1234, they were conquered by the Mongol Empire.

W

WThe Kaiyuan Tongbao, sometimes romanised as Kai Yuan Tong Bao or using the archaic Wade-Giles spelling K'ai Yuan T'ung Pao, was a Tang dynasty cash coin that was produced from 621 under the reign of Emperor Gaozu and remained in production for most of the Tang dynasty until 907. The Kaiyuan Tongbao was notably the first cash coin to use the inscription tōng bǎo (通寶) and an era title as opposed to have an inscription based on the weight of the coin as was the case with Ban Liang, Wu Zhu and many other earlier types of Chinese cash coins. The Kaiyuan Tongbao's calligraphy and inscription inspired subsequent Central Asian, Japanese, Korean, Ryūkyūan, and Vietnamese cash coins and became the standard until the last cash coin to use the inscription "通寶" was cast until the early 1940s in French Indochina.

W

WKangxi Tongbao refers to an inscription used on Manchu Qing dynasty era cash coins produced under the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. Under the Kangxi Emperor the weights and standards of the brass cash coins changed several times and the bimetallic system of Qing dynasty coinage was established. Today Kangxi Tongbao cash coins are commonly used as charms and amulets where different forms of superstition have developed arounds its mint marks and calligraphy.

W

WKnife money is the name of large, cast, bronze, knife-shaped commodity money produced by various governments and kingdoms in what is now China, approximately 2500 years ago. Knife money circulated in China between 600 and 200 B.C. during the Zhou dynasty.

W

WKucha coinage was produced in the Kingdom of Kucha, a Buddhist, Tocharian-speaking state located in the Tarim Basin, during the 1st millennium.

W

WChinese cash coins were first produced during the Warring States period, and they became standardised as the Ban Liang (半兩) coinage during the Qin dynasty which followed. Over the years, cash coins have had many different inscriptions, and the Wu Zhu (五銖) inscription, which first appeared under the Han dynasty, became the most commonly used inscription and was often used by succeeding dynasties for 700 years until the introduction of the Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) during the Tang dynasty. This was also the first time regular script was used as all earlier cash coins exclusively used seal script. During the Song dynasty a large number of different inscriptions was used, and several different styles of Chinese calligraphy were used, even on coins with the same inscriptions produced during the same period. These cash coins are known as matched coins (對錢). This was originally pioneered by the Southern Tang.

W

WLock charms are Chinese numismatic charms shaped like ancient Chinese security locks. Their shape resembles a basket or in most cases the Chinese character for "concave" (凹). The pendants tend to be flat, without any moving parts, or the functionality of the locks they symbolize. They are decorated with both Chinese characters and symbols. Like other types of Chinese numismatic charms, lock charms are meant to protect the wearers from harm, misfortune, and evil spirits, and to bless them with good luck, longevity, and a high rank. In particular, this talisman is meant for young boys, to help "lock" them to the earth, to guard them from death.

W

WSir James Haldane Stewart Lockhart, was a British colonial official in Hong Kong and China for more than 40 years. He also served as Commissioner of British Weihaiwei from 1902 to 1921. Additionally, he was a Sinologist who made pioneering translations.

W

WThe Manchukuo yuan was the official unit of currency of the Empire of Manchuria, from June 1932 to August 1945.

W

WThe Yuan of Mengjiang is the monetary unit that was issued in 1937–1945 by several governments of Mengjiang.

W

WChinese coinage in the Ming dynasty saw the production of many types of coins. During the Ming dynasty of China, the national economy was developed and its techniques of producing coinage were advanced. One early period example is the Bronze 1 cash. Obverse: "Hongwu Tongbao" (洪武通寶). Reverse: blank. Average 23.8 mm, 3.50 grams.

W

WMother coins, alternatively known as seed coins or matrix coins, were coins used during the early stages of the casting process to produce Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, and Vietnamese cash coins. As cash coins were produced using sand casting mother coins were first produced to form the basis for all subsequent cash coins to be released into circulation. Under the Han dynasty in China mints started producing cash coins using bronze master moulds to solve inconsistencies in circulating coins, this only worked partially and by the sixth century mother coins were introduced to solve these inconsistencies almost completely. The Japanese adopted the usage of mother coins in the 600s and they were used to manufacture cast Japanese coins until the Meiji period. The mother coin was initially prepared by engraving a pattern with the legend of the cash coin which had to be manufactured. In the manufacturing process mother coins were used to impress the design in moulds which were made from easily worked metals such as tin and these moulds were then placed in a rectangular frame made from pear wood filled with fine wet sand, possibly mixed with clay, and enhanced with either charcoal or coal dust to allow for the molten metal to smoothly flow through, this frame would act as a layer that separates the two parts of the coin moulds. The mother coin was recovered by the people who cast the coins and was placed on top of the second frame and the aforementioned process was repeated until fifteen layers of moulds had formed based on this single mother coin. After cooling down a "coin tree" (錢樹) or long metallic stick with the freshly minted cash coins attached in the shape of "branches" would be extracted from the mould and these coins could be broken off and if necessary had their square holes chiseled clean, after this the coins were placed on a long metal rod to simultaneously remove the rough edges for hundreds of coins and then these cash coins could be strung together and enter circulation.

W

WOpen-work charms are a type of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese numismatic charms characterised by irregularly shaped "holes" or "openings" between their design elements known as openwork. The design of the amulets represent yin while the holes represent yang and their general purpose was to attract good fortune and ward off evil spirits and misfortune. Unlike most other types of Chinese numismatic charms which usually tend to have square center holes if they’re holed, open-work charms tend to almost exclusively have round center holes though open-work charms with square center holes are known to exist and certain thematic open-work charms that feature human-made constructions mostly told to have square holes. Another distinctive feature of open-work charms is that they’re almost purely based on illustrative imagery and only a small minority of them contain legends written in Hanzi characters. While most other forms of Chinese numismatic charms are made from brass open-work charms are predominantly made from bronze.

W

WThe paper money of the Qing dynasty was periodically used alongside a bimetallic coinage system of copper-alloy cash coins and silver sycees; paper money was used during different periods of Chinese history under the Qing dynasty, having acquired experiences from the prior Song, Jin, Yuan, and Ming dynasties which adopted paper money but where uncontrolled printing led to hyperinflation. During the youngest days of the Qing dynasty paper money was used but this was quickly abolished as the government sought not to repeat history for a fourth time; however, under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor, due to several large wars and rebellions, the Qing government was forced to issue paper money again.

W

WQianlong Tongbao is an inscription used on cash coins produced under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty. Initially the Qianlong Tongbao cash coins were equal to its predecessors in their weight and quality but as expensive military expenditures such as the Ten Great Campaigns began to take their financial toll on the government of the Qing dynasty the quality of these cash coins started to steadily decrease. The weight of the Qianlong Tongbao was changed several times and tin was added to their alloy to both reduce costs and to prevent people from melting down the coins to make utensils. As the intrinsic value of these coins was higher than their nominal value many provincial mints started reporting annual losses and were forced to close down, meanwhile the copper content of the coinage continued to be lowered while the copper mines of China were depleting. The Qianlong era also saw the conquest of Xinjiang and the introduction of cash coins to this new region of the Qing Empire.

W

WQing dynasty coinage was based on a bimetallic standard of copper and silver coinage. The Manchu-led Qing dynasty was established in 1636 and ruled over China proper from 1644 until it was overthrown by the Xinhai Revolution in 1912. The Qing dynasty saw the transformation of a traditional cash coin based cast coinage monetary system into a modern currency system with machine-struck coins, while the old traditional silver ingots would slowly be replaced by silver coins based on those of the Mexican peso. After the Qing dynasty was abolished its currency was replaced by the Chinese yuan of the Republic of China.

W

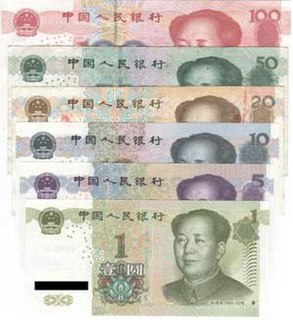

WThe renminbi is the official currency of the People's Republic of China and one of the world's reserve currencies, ranking as the eighth most traded currency in the world as of April 2019.

W

WThe Shanghai Museum is a museum of ancient Chinese art, situated on the People's Square in the Huangpu District of Shanghai, China. Rebuilt at its current location in 1996, it is considered one of China's first world-class modern museums.

W

WThe currency of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom consisted of Chinese cash coins and paper money, although the rarity of surviving Taiping paper money suggests that not much was produced. The first cash coins of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom were issued in the year 1853 in the capital of Tianjing. The cash coins of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom should not be confused with the Taiping Tongbao (太平通寳) which was issued during the Northern Song dynasty between the years 976 and 997, or with any other contemporary rebel coinage that also bear this inscription.

W

WThe Southern Song dynasty refers to an era of the Song dynasty after Kaifeng was captured by the Jurchen Jin dynasty in 1127. The government of the Song was forced to establish a new capital city at Lin'an which wasn't near any sources of copper so the quality of the cash coins produced under the Southern Song significantly deteriorated compared to the cast copper-alloy cash coins of the Northern Song dynasty. The Southern Song government preferred to invest in their defenses while trying to remain passive towards the Jin dynasty establishing a long peace until the Mongols eventually annexed the Jin before marching down to the Song establishing the Yuan dynasty.

W

WThe coinage of the Southern Tang kingdom consisted mostly of bronze cash coins while the coinages of previous dynasties still circulated in the Southern Tang kingdom most of the cash coins issued during this period were cast in relation to these being valued as a multiple of them.

W

WSpade money was an early form of coin and commodity money used during the Zhou dynasty of China. Spade money was shaped like a spade or weeding tool, but the thin blade and small sizes of spade money indicate that it had no utilitarian function. The earlier versions of spade coins tended to have a fragile, hollow socket, reminiscent of a metal shovel. Later versions of spade money had this socket was transformed into a thin, flat piece, and over time, inscriptions were added to the spade coins to mark their denominations. Several versions of spade money circulated across the Chinese Central Plains during the Zhou dynasty period until they were abolished by the Qin dynasty in 221 BC in favour of the Ban Liang cash coins.

W

WA string of cash coins refers to a historical Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, and Vietnamese currency unit that was used as a superunit of the Chinese cash, Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn currencies. The square hole in the middle of cash coins served to allow for them to be strung together in strings, the term would later also be used on banknotes and served there as a superunit of wén (文).

W

WA sycee or yuanbao (Chinese: t 元寶, s 元宝, p yuánbǎo, lit. 'valuable treasure') was a type of gold and silver ingot currency used in imperial China from its founding under the Qin dynasty until the fall of the Qing in the 20th century. Sycee were not made by a central bank or mint but by individual goldsmiths or silversmiths for local exchange; consequently, the shape and amount of extra detail on each ingot were highly variable. Square and oval shapes were common, but boat, flower, tortoise and others are known. Their value—like the value of the various silver coins and little pieces of silver in circulation at the end of the Qing dynasty—was determined by experienced moneyhandlers (shroffs), who estimated the appropriate discount based on the purity of the silver and evaluated the weight in taels and the progressive decimal subdivisions of the tael.

W

WIron cash coins are a type of Chinese cash coin that were produced at various times during the monetary history of imperial China as well as in Japan and Vietnam. Iron cash coins were often produced in regions where the supply of copper was insufficient, or as a method of paying for high military expenditures at times of war, as well as for exports at times of trade deficits.

W

WThe Western Xia was a Tangut-led Chinese dynasty which ruled over what are now the northwestern Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, eastern Qinghai, northern Shaanxi, northeastern Xinjiang, southwest Inner Mongolia, and southernmost Outer Mongolia from 1032 until 1227 when they were destroyed by the Mongols. The country was established by the Tangut people; likewise its earliest coins were escribed with Tangut characters, while later they would be written in Chinese. Opposed to Song dynasty coins that often read top-bottom-right-left, Western Xia coins exclusively read clockwise. Despite the fact that coins had been cast for over a century and a half, very little were actually produced and coins from Western Xia are a rarity today. Although the Western Xia cast their own coins barter remained widely used.

W

WWu Zhu is a type of Chinese cash coin produced from the Han dynasty in 118 BC when they replaced the earlier San Zhu cash coins, which had replaced the Ban Liang (半兩) cash coins a year prior, until they themselves were replaced by the Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) cash coins of the Tang dynasty in 621 AD. The name Wu Zhu literally means "five zhu" which is a measuring unit officially weighing about 4 grams however in reality the weights and sizes of Wu Zhu cash coins varied over the years. During the Han dynasty a very large quantity of Wu Zhu coins were cast but their production continued under subsequent dynasties until the Sui.

W

WXin dynasty coinage was a system of Ancient Chinese coinage that replaced the Wu Zhu cash coins of the Han dynasty and was largely based on the different types of currencies of the Zhou dynasty, including Knife money and Spade money. During his brief reign, Wang Mang introduced a total of four major currency reforms which resulted in 37 different kinds of money consisting of different substances, different patterns, and different denominations.

W

WThe Yongle Tongbao was a Ming dynasty era Chinese cash coin produced under the reign of the Yongle Emperor. As the Ming dynasty didn't produce copper coinage at the time since it predominantly used silver coins and paper money as the main currency, the records vary on when the Yongle Emperor ordered its creation between 1408 and 1410, this was done as the production of traditional cash-style coinage had earlier ceased in 1393. The Yongle Tongbao cash coins were notably not manufactured for the internal Chinese market where silver coinage and paper money would continue to dominate, but were in fact produced to help stimulate international trade as Chinese cash coins were used as a common form of currency throughout South, Southeast, and East Asia.

W

WThe Yuan dynasty was a Mongol-ruled Chinese dynasty which existed from 1271 to 1368. After the conquest of the Western Xia, Western Liao, and Jin dynasties they allowed for the continuation of locally minted copper currency, as well as allowing for the continued use of previously created and older forms of currency, while they immediately abolished the Jin dynasty's paper money as it suffered heavily from inflation due to the wars with the Mongols. After the conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, the Yuan dynasty started issuing their own copper coins largely based on older Jin dynasty models, though eventually the preferred Yuan currency became the Jiaochao and silver sycees, as coins would eventually fall largely into disuse. Although the Mongols at first preferred to have every banknote backed up by gold and silver, high government expenditures forced the Yuan to create fiat money in order to sustain government spending.

W

WThe Zhaona Xinbao is a special type of Southern Song dynasty cash coin developed as a propaganda and psychological warfare tool for recruiting defectors from the army of the Jurchen Jin dynasty around the year Shaoxing 1 under the reign of Emperor Gaozong. These special coins superficially resemble traditional Chinese cash coins but contain an inscription alluding to their intent, generally these Zhaona Xinbao tokens were made from bronze but in very rare cases they were also made from silver or gold.

W

WThe Zhengde Tongbao is a fantasy cash coin, Chinese, and Vietnamese numismatic charm bearing an inscription based on the reign title of the Zhengde Emperor of the Ming dynasty. The Zhengde Emperor reigned from the year 1505 until 1521, however during this period no circulating cash coins were minted. There were a large amount "cash coins" bearing the Zhengde era name are minted from the late Ming to early Qing dynasty periods as superstitious "lucky coins" with auspicious depictions and instructions, as this inscription remained popular for charms modern reproductions of the Zhengde Tongbao are also very common.

W

WStandard cash, or regulation cash coins, is a term used during the Ming and Qing dynasties of China to refer to standard issue copper-alloy cash coins produced in imperial Chinese mints according to weight and composition standards that were fixed by the imperial government. The term was first used for Hongwu Tongbao cash coins following the abolition of large denomination versions of this cash coin series.

W

WThe Zhuangpiao, alternatively known as Yinqianpiao, Huipiao, Pingtie (憑帖), Duitie (兌帖), Shangtie (上帖), Hupingtie (壺瓶帖), or Qitie (期帖) in different contexts, refer to privately produced paper money made in China during the Qing dynasty and early Republic of China periods issued by small private banks known as qianzhuang. Other than banknotes qianzhuang also issued Tiexian.