W

WThe Committee of General Security was a French parliamentary committee which acted as police agency during the French Revolution. Along with the Committee of Public Safety it oversaw the Reign of Terror. The Committee of General Security supervised the local police committees in charge of investigating reports of treason, and was one of the agencies with authority to refer suspects to the Revolutionary Tribunal for trial and possible execution by guillotine.

W

WThe Committee of Public Safety formed the provisional government in France, led mainly by Maximilien Robespierre, during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), a phase of the French Revolution. Supplementing the Committee of General Defence created after the execution of King Louis XVI in January 1793, the Committee of Public Safety was created in April 1793 by the National Convention and restructured in July 1793. It was charged with protecting the new republic against its foreign and domestic enemies, fighting the First Coalition and the Vendée revolt. As a wartime measure, the committee was given broad supervisory and administrative powers over the armed forces, judiciary and legislature, as well as the executive bodies and ministers of the Convention.

W

WThe Cult of Reason was France's first established state-sponsored atheistic religion, intended as a replacement for Catholicism during the French Revolution. After holding sway for barely a year, in 1794 it was officially replaced by the rival Cult of the Supreme Being, promoted by Robespierre. Both cults were officially banned in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte with his Law on Cults of 18 Germinal, Year X.

W

WThe Death of Marat is a 1793 painting by Jacques-Louis David of the murdered French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat. It is one of the most famous images of the French Revolution. David was the leading French painter, as well as a Montagnard and a member of the revolutionary Committee of General Security. The painting shows the radical journalist lying dead in his bath on 13 July 1793, after his murder by Charlotte Corday. Painted in the months after Marat's murder, it has been described by T. J. Clark as the first modernist painting, for "the way it took the stuff of politics as its material, and did not transmute it".

W

WThe Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1793 is a French political document that preceded that country's first republican constitution. The Declaration and Constitution were ratified by popular vote in July 1793, and officially adopted on 10 August; however, they never went into effect, and the constitution was officially suspended on 10 October. It is unclear whether this suspension was thought to affect the Declaration as well. The Declaration was written by the commission that included Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just and Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles during the period of the French Revolution. The main distinction between the Declaration of 1793 and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 is its egalitarian tendency: equality is the prevailing right in this declaration. The 1793 version included new rights, and revisions to prior ones: to work, to public assistance, to education, and to resist oppression.

W

WThe Federalist revolts were uprisings that broke out in various parts of France in the summer of 1793, during the French Revolution. They were prompted by resentments in France's provincial cities about increasing centralisation of power in Paris, and increasing radicalisation of political authority in the hands of the Jacobins. In most of the country the trigger for uprising was the exclusion of the Girondins from the Convention after the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793. Although they shared common origins and political objectives, the revolts were not centrally organised or well-coordinated. The revolts failed to win any sustained popular support and were put down by the armies of the Convention over the following months. The Reign of Terror was then imposed across France to punish those associated with them and to enforce Jacobin ideology.

W

WThe Constitution of 1793, also known as the Constitution of the Year I or the Montagnard Constitution, was the second constitution ratified for use during the French Revolution under the First Republic. Designed by the Montagnards, principally Maximilien Robespierre and Louis Saint-Just, it was intended to replace the constitutional monarchy of 1791 and the Girondin constitutional project. With sweeping plans for democratization and wealth redistribution, the new document promised a significant departure from the relatively moderate goals of the Revolution in previous years.

W

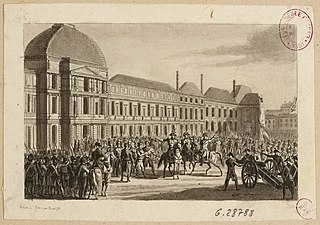

WThe insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, during the French Revolution, resulted in the fall of the Girondins in the National Convention under pressure of the Parisian sans-culottes, Jacobins of the clubs, and Montagnards. By its impact and importance, this insurrection stands as one of the three great popular insurrections of the French Revolution, following those of 14 July 1789 and 10 August 1792. the principal conspirators were Enragés Dobson and Varlet; Pache and Chaumette would lead the march on the Convention.

W

WLe souper de Beaucaire was a political pamphlet written by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1793. With the French Revolution into its fourth year, civil war had spread across France between various rival political factions. Napoleon was involved in military action, on the government's side, against some rebellious cities of southern France. It was during these events, in 1793, that he spoke with four merchants from the Midi and heard their views. As a loyal soldier of the Republic he responded in turn, set on dispelling the fears of the merchants and discouraging their beliefs. He later wrote about his conversation in the form of a pamphlet, calling for an end to the civil war.

W

WLevée en masse is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

W

WThe execution of Louis XVI by guillotine, a major event of the French Revolution, took place publicly on 21 January 1793 at the Place de la Révolution in Paris. At a trial on 17 January 1793, the National Convention had convicted the king of high treason in a near-unanimous vote; while no one voted "not guilty", several deputies abstained. Ultimately, they condemned him to death by a simple majority. The execution was performed four days later by Charles-Henri Sanson, then High Executioner of the French First Republic and previously royal executioner under Louis.

W

WThe drownings at Nantes were a series of mass executions by drowning during the Reign of Terror in Nantes, France, that occurred between November 1793 and February 1794. During this period, anyone arrested and jailed for not consistently supporting the Revolution, or suspected of being a royalist sympathizer, especially Catholic priests and nuns, was cast into the river Loire and drowned on the orders of Jean-Baptiste Carrier, the representative-on-mission in Nantes. Before the drownings ceased, as many as four thousand or more people, including innocent families with women and children, died in what Carrier himself called "the national bathtub".

W

WThe National Convention was a parliament of the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the one-year Legislative Assembly. Created after the great insurrection of 10 August 1792, it was the first French government organized as a republic, abandoning the monarchy altogether. The Convention sat as a single-chamber assembly from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795.

W

WThe Paris Commune during the French Revolution was the government of Paris from 1789 until 1795. Established in the Hôtel de Ville just after the storming of the Bastille, it consisted of 144 delegates elected by the 60 divisions of the city. Before its formal establishment, there had been much popular discontent on the streets of Paris over who represented the true Commune, and who had the right to rule the Parisian people. The first mayor was Jean Sylvain Bailly, a relatively moderate Feuillant who supported constitutional monarchy. He was succeeded in November 1791 by Pétion de Villeneuve after Bailly's unpopular use of the National Guard to disperse a riotous assembly in the Champ de Mars.

W

WThe Reign of Terror, commonly called The Terror, was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, anticlerical sentiment, and accusations of treason by the Committee of Public Safety.

W

WDuring the French Revolution, a représentant en mission was an extraordinary envoy of the Legislative Assembly (1791–92) and its successor the National Convention (1792–95). The term is most often assigned to deputies designated by the National Convention for maintaining law and order in the départements and armies, as they had powers to oversee conscription into the army, and were used to monitor local military command. At the time France was in crisis; not only was war going badly, as French forces were being pushed out of Belgium, but also there was revolt in the Vendée over conscription into the army and resentment of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

W

WRepublican marriage was a method of execution that allegedly occurred in Nantes during the Reign of Terror in Revolutionary France and "involved tying a naked man and woman together and drowning them". This was reported to have been practised during the drownings at Nantes (noyades) that were ordered by local Jacobin representative-on-mission Jean-Baptiste Carrier between November 1793 and January 1794 in the city of Nantes. Most accounts indicate that the victims were drowned in the river Loire, although a few sources describe an alternative means of execution in which the bound couple is run through with a sword, either before, or instead of drowning.

W

WThe Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution from 1789 to 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which surprisingly supported the French aristocracy. Because he had supported the American colonists in their rebellion against Great Britain, his views sent a shockwave through the country. Many writers responded to defend the French Revolution, such as Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Alfred Cobban calls the debate that erupted "perhaps the last real discussion of the fundamentals of politics" in Britain. The themes articulated by those responding to Burke would become a central feature of the radical working-class movement in Britain in the 19th century and of Romanticism. Most Britons celebrated the storming of the Bastille in 1789 and believed that Kingdom of France should be curtailed by a more democratic form of government. However, by December 1795, after the Reign of Terror and the War of the First Coalition, few still supported the French cause.

W

WThe revolutionary sections of Paris were subdivisions of Paris during the French Revolution. They first arose in 1790 and were suppressed in 1795.

W

WThe Revolutionary Tribunal was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the most powerful engines of the Reign of Terror.

W

WThe Society of the Friends of the Blacks was a French abolitionist society founded during the late 18th century. The society's aim was to abolish both the institution of slavery in the France's overseas colonies and French involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. The society was founded in Paris in 1788, and remained active until 1793, during the midst of the French Revolution. It was led by Jacques Pierre Brissot, who frequently received advice from British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who led the abolitionist movement in Great Britain. At the beginning of 1789, the Society had 141 members.

W

WThe trial of Louis XVI—officially called "Citizen Louis Capet" since being dethroned—before the National Convention in December 1792 was a key event of the French Revolution. He was convicted of high treason and other crimes, resulting in his execution.

W

WThe War in the Vendée was a counter-revolution from 1793 to 1796 in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the river Loire in Western France. Initially, the war was similar to the 14th-century Jacquerie peasant uprising, but quickly acquired themes considered by the Jacobin government in Paris to be counter-revolutionary and Royalist. The uprising headed by the newly formed Catholic and Royal Army was comparable to the Chouannerie, which took place in the area north of the Loire.